Imagine hearing the lunch bell ring. Instead of running to the cafeteria, you run to the school library, arriving just in time for the ... zombie apocalypse?

You have just entered teacher-librarian Amy Wilde’s library at Cascade Middle School in Bend, Ore.

Imagine that your high school classes have been cut short so you can attend an assembly to listen to Jay Asher, acclaimed author of Thirteen Reasons Why, speak. On another day, the guest speaker is Michelle Lesniak, 2013 winner of Project Runway, or a photo- journalist whose work documents the Black Panther Party. These speakers have all been brought to the school as a part of an author visit program spearheaded by Paige Battle, teacher-librarian at Grant High School.

Or imagine you are an elementary student challenged to par- ticipate in the competitive reading program known as Battle of the Books by Ridgeview Elementary School teacher-librarian Karen Babcock, whose principal believes unfailingly in the importance of fully funded school libraries.

Now, imagine you attend school in a building that has cut library funding so severely that there is no certi ed teacher-librarian at the helm. The book budget has been decimated. So has the technology budget. If you’re lucky, a library assistant remains to help you check out materials — but only if you’re lucky.

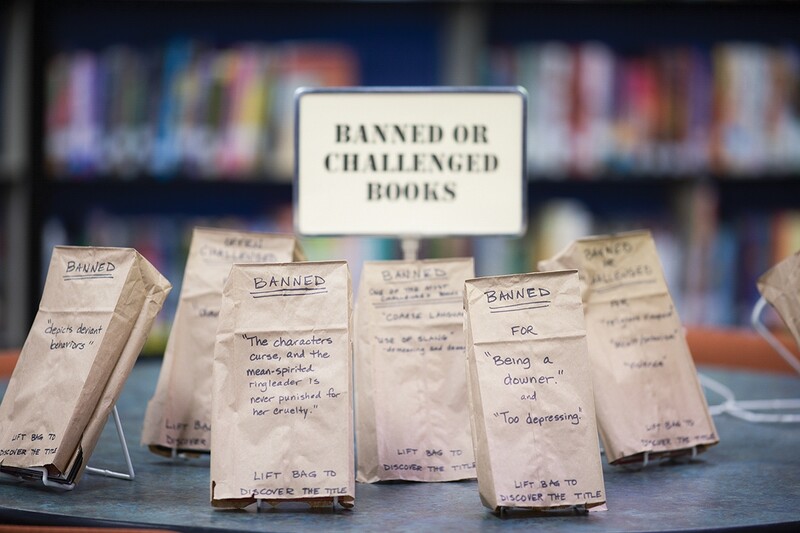

A Banned Book display peaks students' interest in the library at Cascade Middle School in Bend.

This final bleak scenario is reality for the majority of students in Oregon since the 2007 recession. Only Oregon’s luckiest (read: most often wealthiest) students have access to fully qualified teacher-librarians and well- resourced libraries, once again placing students in poverty at a disadvantage.

This is in spite of the fact that access to teacher-librarians is proven time and again to improve student learning.

Despite a rebounding economy in which schools are starting to re-invest in many of the programs cut during the economic downturn, school library programs have been left to stagnate, and students are suffering.

Oregon’s teacher-librarians are ghting back.

At the OEA Representative Assembly in April 2016, member Tricia Snyder, a teacher-librarian at Reynolds Middle School in Multnomah County, crafted a New Business Item seeking to conduct a study of student access to both teacher-librarians and library resources in Oregon. The study was ap- proved and is well under way. Initial data is confirming what nationwide studies have al- ready shown conclusively — teacher-librarians are vital to a school’s success. Without them, students su er.

“In my own district, I’ve seen music specialists brought back, PE specialists brought back,” Snyder says, noting that these are not all full-time positions. “But the library has still not been discussed. It’s (seen as) important, but it’s never important enough to make it back on the table.”

Her mission, then, in crafting the NBI is to bring awareness to the trends plaguing Oregon’s teacher-librarians that are to the detriment of students.

Many students at Cascade Middle School spend their lunch hour in the library with teacher-librarian Amy Wilde.

Oregon’s libraries are under-staffed

In 1980, there were 880 full time teacher-librarians employed in Oregon schools. By 2014, that number dropped to 144, accord- ing to a report released in 2014 by the Oregon Association of School Libraries (OASL).

Put another way, the number of licensed school librarians in Oregon has dropped by 61 percent since 1980, while the number of students per librarian has more than tripled, according to the Quality Education Mode (QEM) and School Libraries' 2011 annual report.

Jen Maurer, school library consultant for the state of Oregon, explains that the QEM was the Oregon Legislature’s attempt to determine the level of funding necessary to fund a best-practice prototypical school.

The QEM created three “prototype” schools (elementary, middle, and high school) and drew out detailed, itemized bud- gets.

“They do, in that model, have three points that speak to school library programs. One is how many FTE of licensed librarians you would have, one is about support staff in the schools, and the third is how much you would spend on books and periodicals, all together, print or electronic, per student,” she says.

Maurer says that in 2011, the last year the QEM library data was analyzed, only ve schools met the QEM’s library funding levels. Many teacher-librarians will tell you that the ideal level of staffing for school libraries is at least one full time teacher-librarian and one full time library assistant per building. These two employees, one certified, one support professional, often work in tandem with a textbook clerk, local library volunteers, and student aides.

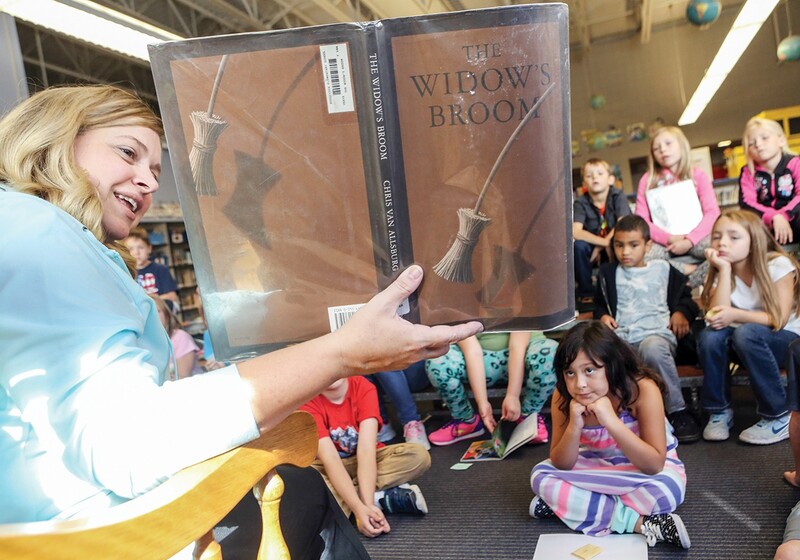

Karen Babcock, a librarian at Ridgeview Elementary School in Spring eld reads to students.

Only then can the school library function most effectively.

“The research is clear on what makes a difference in academic achievement, and what makes a difference in academic achievement is a school library that is staffed by a teach- er-librarian, supported by classiffied library manager or library technician,” says Anne Urban, the district librarian for Three Rivers School District in Josephine County.

The research is also clear that a full-time teacher-librarian on staff results in higher academic performance as measured by reading test scores, according to the 2016 edition of School Libraries Work! A Compendium of Research Supporting the Effectiveness of School Libraries.

The problem is, many people don’t understand what it is, exactly, that a teacher- librarian does.

A teacher-librarian goes by many names including school librarian and library media specialist. Both are accurate terms, but teacher-librarian is how Oregon’s school librarians refer to themselves because the hyphenated job title describes both aspects of the profession.

Like any librarian you would find in a public library, teacher-librarians are information specialists, helping the public find and access information. They are research experts, and as information expands to other mediums (including all the resources of the digital age), they must be experts at accessing information in various print and electronic forms.

Librarians also exist to help guard the principles of free speech in a democratic society and they help connect readers with books that will open them to the joy of reading.

Teacher-librarians do all that and more. They are certified teachers who have added a library media endorsement to their teaching credentials. In addition to their “librarian” duties, teacher-librarians wear a “teacher” hat, too. They teach students to use media and do research. These skills are becoming more and more critical in a 21st-century society in which students are bombarded by information from sources that aren’t always reliable.

Teacher-librarians even have their own state standards covering information literacy, reading engagement, social responsibility, and technology integration.

“The role of a teacher-librarian in today’s school is different than it was 20 or 30 years ago. It's to be an instructional leader,” Urban says. “It’s to help create a culture of literacy to support teachers in integrating instructional technology into their practice; it’s to help teachers and students learn to be ex- perts at digital citizenship and looking at information.”

When a library assistant works with a teacher-librarian, several educational opportunities exist at once. The teacher-librarian can visit a classroom and conduct a lesson on research skills while the library stays open, allowing the library assistant to make book recommendations and check out books.

Today, the reality in many schools is a library staffed by an education support professional making a valiant effort to keep the library afloat. This is simply not adequate, and students suffer as a result.

Oregon’s libraries are under-resourced

“The technology in my library is abysmal,” says Snyder, the impetus behind the OEA library study. While funding is scarce for school library staff, the story is no different when it comes to new materials and technology.

And in a world where technology changes rapidly, the inability to update library and technology collections with new materials becomes a very real problem for students who need to navigate this tech for their future careers.

With a lack of new technology or access to a professional to help them navigate, Oregon’s students are showing up to college without the research skills necessary to thrive.

Anne-Marie Deitering, associate univer- sity librarian for learning services at OSU, works with incoming college freshmen and while she has noticed a willingness to dive into research, she says students don’t really know what to do when their rst search does not yield answers.

“Students tend of come in with a fairly high comfort level with finding information and finding answers. It’s not necessarily a very deep knowledge,” she says. “They don’t necessarily have experience with a lot of different discourses or a lot of different types of sources.”

The unfortunate reality for many public school students today is that they have been without a teacher-librarian for so long that they don’t even know what resources they are missing.

Maurer relays a conversation she had with a parent in the Beaverton School District who played an instrumental role in that district’s recent decision to re-prioritize library spending.

“And she said to me, ‘The sad part is, if we wait too long and we go any more years without having a librarian, I have no parents to talk to who understand what a librarian would be doing and could be doing,’” Maurer says. “They have no frame of reference at that point. And I think that’s what’s sad, is that with the years of lack of library pro- grams in Oregon, there’s no point of reference for the majority of parents, the majority of teachers, the majority of administrators.”

Deitering agrees, mourning the loss not just of library staff and resources but also a loss of cultural awareness around the function libraries play in society.

“When they’re not in schools, we lose the idea of libraries as a common good, which means we are less likely to have them in the university, we’re less likely to have them in the community. Most of what we do in school is very, very heavily focused on rewarding [students for] knowing things and penalizing [them for] not knowing things. I think we teach people to be afraid to show that they don’t know things, but libraries are a safe space to not know things,” Deitering says.

Teaching research skills in a way that encourages genuine inquiry is a skill all college-bound students need. It’s hard to teach, and while subject-area teachers don’t have this training, teacher-librarians do. They are experts at teaching research, but in order to teach that authentic inquiry, they must have cutting-edge technology tools, tools that students will be expected to successfully navigate at the college level — tools that many Oregon schools aren’t funding.

“It comes down to the fact that we are trying to build independent thinkers. That’s the core of what school libraries do,” Maurer says. “Advanced search skills are not easy to come by.”

Site-based management creates equity issue

For many teacher-librarians, the real rub is that students who would bene t the most from a well-resourced, well-staffed school library are the least likely to have access to one.

“Poor children and children of color are least likely to have access to a high-quality library program, and the research shows they are the most likely to bene t,” says Urban.

In part, this has to do with the amount of adult guidance a child receives in a library. Middle class children are more likely to have reading role models at home than children who live in poverty. This becomes a significant problem at the middle primary grades when, Urban explains, a drop-o in reading occurs. "The number one reason kids stop reading is that they don’t know what to read next," says Urban, citing research done by Scholastic.

"Whereas middle class children will go to the library and receive help from their parents in picking a book to read, poor children and children of color are [disproportionately] more likely to not have a lot of guidance when they're in a library," she says, speaking to equity issues at play in access to library services.

In 1980 there were 880 full time teacher-librarians employed in Oregon schools. By 2014 that number dropped to 144.

Exemplary school library programs set the standard

Wilde’s lunchtime library zombie apocalypse, along with her other lunch and after- school programs, is just one instance of an exemplary Oregon school library program. Whether it’s due to a supportive principal or a teacher-librarian who has figured out how to do more with less, there are school libraries across the state that serve as exemplars that all districts can strive toward.

The zombie apocalypse was a clever ruse to teach students wilderness survival skills — and to suck them into the library. Wilde invited in a wilderness survival expert from the local community college, who trans- formed the library into a post-apocalyptic scene complete with tents, food rations, and all kinds of survival gear.

Students were divided into table groups where their wilderness survival skills were put to the test. A winner emerged at each of the two lunches, and those lucky students carried away survival packs stuffed with food rations, bandanas, Band-Aids and other assorted survival gear. All student participants received an “I survived the zombie apocalypse at Cascade Middle School” bumper sticker.

“We got kids in there that normally wouldn’t be in the library at lunch,” Wilde says.

A persistent stereotype exists in the world of all librarians, Maurer explains. It’s rare to run across a pop culture depiction of a librarian who isn’t “shushing ” people. As a result, the general public tends to see all librarians as stuffy folks who demand whispering while they check out books. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Teacher-librarians are experts at packaging information so that the mundane becomes exciting.

“I hated the stuff that I teach,” Wilde says about herself as a student. “I didn’t like to do research. It wasn’t made exciting and interesting to me. When I teach I try to put myself in those shoes. I want my lessons to be able to connect.”

Babcock’s lessons certainly connect with her elementary school students. She won her district’s Certified Teacher of the Year award last year for Ridgeview Elementary School’s library program. She describes her two pet projects as Oregon’s Battle of the Books, a reading competition in which participants read selected books and answer questions about their reading, and Book- Tubes, a project in which students make promotional videos for books.

Babcock attributes much of her success to collaboration with her principal, Jim Crist, who asked her when she started working for him, “What do you want? What’s your dream job?”

Together, Babcock says they hatched out a plan to enhance, through a focus on instructional technology, the learning experience of students.

Babcock knows she is succeeding when students are excited to spend time in the library.

“It’s not just a warehouse of books. You need somebody who breathes life into it,” she says.

Paige Battle and Nancy Sullivan, both teacher-librarians for Portland Public Schools, know a little something about motivating students. They run complementary programs in their respective schools; Battle is passionate about her author visit program and Story Slam, while Sullivan runs a popular poetry slam program.

“Every day in the Madison Library is different, often radically so, depending on the time of year and where classroom teachers are with curriculum, research assignments, and other projects,” Sullivan says, describing the library at Madison High School.

Karen Babcock, teacher-librarian at Ridgeview Elementary School in Spring eld, won her district's Certi ed Teacher of the Year award for her e orts in the school library.

“For example, today our History of Portland classes are hosting a World’s Fair in the library. Students have created poster board displays based on their research of the 1905 “World’s Fair,” or Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Calliope music is playing, the diameter of the largest tree in Oregon at the time is taped off on the floor, there are displays representing attractions from the exposition. Classroom teachers are bringing groups through to learn from the students in the class.”

Advocating for school libraries and ESSA

While Oregon’s school libraries have been in a state of emergency for nearly a decade, there are some positive signs of change.

Because of tireless advocacy from passionate teachers, librarians, and parents, some school districts are re-investing in school library programs.

Both Portland Public Schools and the Beaverton School District brought back numerous teacher-librarians in 2015.

“There has been a push over the last few years to reinstate at all levels,” Battle says.

It’s not just big districts that are refocusing on school libraries. The Three Rivers School District in rural Josephine County is small, yet has made it a priority to begin strengthening the school library program. One important step was the hiring of Urban, the district’s librarian. Her job is to support all 13 school libraries in the district.

One goal the district is working toward is collaboration between classroom teachers and teacher-librarians.

“My district and school board have been very supportive of that connection,” Urban says. “One challenge is how do we find the funds to support it?”

There has recently been a glimmer of hope in that arena.

The Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (ESSA), which replaced No Child Left Behind, specifically includes teacher-librarians and high-quality libraries as eligible for uses for some federal dollars.

“School librarians are mentioned in a few places in the law, where they have never been mentioned before,” Maurer explains, adding that there’s a national effort in place to help departments of education understand that ESSA supports library funding.

All the necessary elements are now in place to make a strong push to reinstate teacher-librarians in Oregon schools:

- School librarians ease the workload of classroom teachers by shouldering one of the most challenging aspects of instruction, teaching research.

- Studies demonstrate conclusively that teacher-librarians mean higher state test scores at all grade levels.

- ESSA provides language supporting districts using federal funds to staff and outfit school libraries.

While these three elements taken together o er a compelling case for fully reinvesting in school libraries, librarians need the help of classroom teachers to advocate for their return.

The key to a librarian’s success lies in collaboration with classroom teachers and administrators.

After a successful collaboration, Battle recommends sharing success stories far and wide.

“Share those stories with people who make decisions, so that the teacher-librarian doesn’t have to toot their own horn,” she says.