There have been moments over the last year that have seemed surreal for Nicole Butler-Hooton — like when she walked through the front doors of the White House last month to be greeted by First Lady Dr. Jill Biden for a special event honoring the State and National Teachers of the Year.

Butler-Hooton, a proud member of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz and the San Carlos Apache tribe of Arizona, was named the 2021 Oregon Teacher of the Year in the Fall of 2020. She speaks of her experience in Washington D.C. in a way that reflects her most ardent values as an Indigenous educator. In a post of her outside the White House on her Teacher of the Year Instagram account, Butler-Hooton wrote, “Today was one of the most beautiful days to celebrate teachers and all they bring to their communities. Our voices were heard today and we felt seen. Oregon teachers, I share this with you... I have work to do to strengthen the Indigenous presence in today’s classroom, and I’m ready.”

Her experience at the White House and her meetings that followed at the U.S. Capitol with Sen. Wyden and Sen. Merkley will stay with Butler- Hooton long after her time as Teacher of the Year comes to an end this Fall. And yet, for the Eugene-area teacher, the equity issues she discussed that day in Washington D.C. have been her passion since her career began as a teacher a little over 15 years ago — and they are anything but surreal. They are her own lived experience as a student and now teacher of color in Oregon.

In thinking about strategies to support the work of diversifying the educator workforce, Butler-Hooton reflects on the experience she had as Native student growing up in a predominantly white community. “I didn’t see teachers or students who looked like me. I didn’t see curriculum being used that was accurate to my experience. I’ve really focused on how we can humanize the curriculum and create classrooms of love and joy, justice and social justice,” she says. “My experience as a Native teacher now is about finding my voice to disrupt practices that I don’t feel are equitable for my students, especially those in marginalized groups. I’ve seen the effect in these limitations and so I really strive to create connections that transcend our classrooms.”

Up until this year, Butler taught second grade at Irving Elementary in the Bethel School District, but this year, she’s shifted gears and taken on a new TOSA role, focused on providing support to new teachers in the district. Her work is fueled by a critical question: how do we lift up, support, and retain educators of color in the profession? How do we build the pipeline to recruit new BIPOC educators in pursuing a teaching career?

Through OEA’s Educator Empowerment Academy and the Western Regional Educator Network (WREN), Butler- Hooton and a team of other BIPOC educators from Eugene 4J, Bethel and Albany School Districts are tackling these questions as their central “problem of practice.” Using the OEA Empowerment Process, which centers on human-centered design, continuous improvement, and community-based organizing, Butler- Hooton and her team are defining strategies to support and retain BIPOC educators in the classroom, a demographic that is highly susceptible to burnout. A study by the University of Pennsylvania found that teachers of color leave the profession 24 percent more often than white teachers, and NEA cites a declining number of Black and Hispanic students majoring in education that is steeper than the overall decline in education majors.

When she joined OEA’s Empowerment Academy in January 2021, Butler-Hooton had already begun meeting with educators from around Oregon as part of her Teacher of the Year title. Some were surprised she’d decided to take on yet one more responsibility during an already taxing year, but “my heart was in it,” she said. “Thinking about how I got to where I am in my own lived experience — and using that to focus on how we can support our BIPOC teachers. I said yes immediately.” Through her platform as Teacher of the Year, she’d heard with so many teachers of color across the state who needed support. “How are we humanizing our spaces in our curriculum and in our relationships? One thing I know that’s necessary is to have supports in places for our teachers who feel very marginalized and isolated,” she says.

In Bethel and more broadly across Oregon, Butler-Hooton says teachers coming into the profession today receive so much more in the way of anti-racist training and curriculum than she did as a new classroom teacher 15 years ago. Now, with the passage of Senate Bill 13: Tribal History / Shared History in 2017, K-12 educators are given professional development to deliver Native American curriculum that accurately reflects the histories of Oregon’s nine federally recognized Tribes. But training alone does not solve the deep, systemic issues that contribute to a workforce that lags in diversity, especially in contrast to our student populations. This is where the human-centered piece of the puzzle comes into focus.

THE POWER OF EARLY CAREER TEACHERS

Juliauna Greene is in her fifth year of teaching at Fairfield Elementary in Bethel. She fell in love with the school community the moment she walked out of her job interview — accepting the offer to teach there was an easy decision to make. As a child growing up in Eugene, Greene’s mom, who had a disability, was unable to continue working. “We were very poor. We were on food stamps, disability income and Section 8 housing. I have a lot of students who are in similar situations — most of my students are struggling. But it’s why I love working here, because I really do see myself in them as a students. And I see all the supports that we have for them here at our school, which is really heartening,” Greene says.

She recognizes that as a Black teacher, many of her students of color (she has just a handful) conversely see themselves represented in her — an experience she didn’t have until taking an ethnic studies course in college, when she had her first Black instructor.

Greene was fresh into her career when she was asked by Butler-Hooton, her new teacher mentor at the time, to join the work of the OEA Empowerment Academy team. The Team’s “change idea” in addressing their problem of practice was to build a network of support for BIPOC educators. The work began by reaching out to collect feedback from BIPOC teachers across the Western region; that survey data gave way to interest groups, beginning with a time for educators of color to meet and share culturally responsive lesson plans.

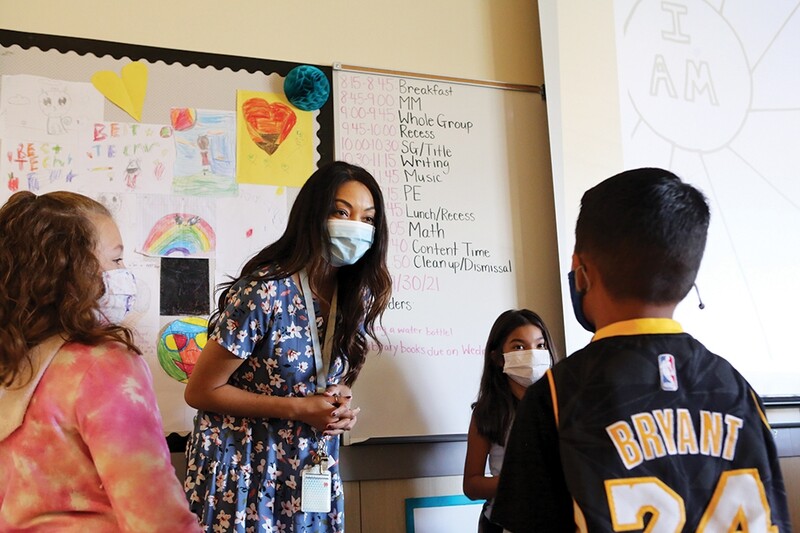

Juliauna Greene teaches a class on identity at Fairfield Elementary in Eugene’s Bethel School District. She loves the close rapport she's been able to develop with her students of color in particular.

While the time was incredibly valuable for Greene as a facilitator, “I was definitely nervous. I had to fight against feeling like it wasn’t my place in be one of the leaders in this type of group setting. But, everyone was so supportive and the experience really built my confidence and truly did make me feel empowered in my practice. To meet all of these other educators who look like me and have similar experiences… to collaborate and bond with them… was a really powerful experience,” she says.

Greene says that putting newer educators into equity leadership positions helps cultivate new ideas and bridge the understanding of what it’s like to be early career, and particularly an early career teacher of color in a system that has long been geared around white, experienced teachers.

“I have a perspective that they don’t necessarily have any more,” Greene says of the isolating experience it can be to walk into a new District as one of the few teachers of color. “This is something I’m living now, and it’s been nice to provide that voice. I feel like I’m stepping up for all my other fellow new educators.”

For Greene, having Butler-Hooton as her mentor has all but eliminated that feeling of isolation, which for many early career teachers has only intensified through the pandemic and online teaching. “She’s Oregon Teacher of the Year, and yet she she’s so humble. She talks to me like we’re on the same level,” Greene says. “Having a mentor of color has just been really valuable and made me feel so supported. I feel like this is a place that I could be for a long time, because I do have that support system with Nicole.”

Nicole Butler-Hooton meets with Juliauna Greene, a BIPOC educator from Fairfield Elementary in Eugene’s Bethel School District. Greene was fresh into her career when she was asked by Butler-Hooton, her new teacher mentor at the time, to join the work of the OEA Empowerment Academy team.

DIVERSIFYING THE FIELD THROUGH TEACHER LEADERSHIP

Norina Andina’s 20-year career in teaching has been largely shaped by her Colombian heritage, although she hasn’t always been a Spanish-speaker. Andina was adopted by white parents at age three from Colombia and raised in Minnesota; she didn’t start taking Spanish classes until middle school. The love of the language was immediate — she chose to earn a dual major in Spanish and Latin American studies, and eventually found her home in the classroom, first as a Spanish teacher for nearly all white students in Eugene, and then as an ELD teacher for students who entered school knowing little to no English at all.

Two years ago, she moved from the Eugene area to Albany (following her children as they enrolled at Oregon State University) and is currently an ELD teacher at Sunrise Elementary, the lowest SES school in the district. About half of her students are Latino, and she’s the only teacher of color in that building. “I take the responsibility deeply. For all the Latino students and students of color to see me and think, ‘Oh, one of us can be a teacher. It’s not just white people. And for the white students — it’s just as important. I might be their only teacher of color they will ever have,” Andina says.

Nationally, according to the US Department of Education, about half of all students in our public schools are non-white, and yet only 20 percent of educators identify as BIPOC. A Center for American Progress study, titled “America’s Leaky Pipeline for Teachers of Color,” reports that “minority teachers have higher expectations of minority students, provide culturally relevant teaching, develop trusting relationships with students, confront issues of racism through teaching, and become advocates and cultural brokers.”

Indeed, having a teacher of color contributes to rising student success rates — but it also shows students of color what’s possible. It shows these students that they have something to offer the teaching profession in return.

Lecturer Sarah Leibel, a master teacher in the Harvard Teacher Fellows (HTF) Program, mentions how, in literature, students need “mirrors and windows” — meaning they can see them themselves in stories and also experience unfamiliar worlds. “It’s really important that students have people who reflect back to them their language, their culture, their ethnicity, their religion. It doesn’t mean all the people in their lives have to do that mirroring, but they should have some. And we know that in the teaching profession, there really are not enough mirrors,” Leibel says.

When Andina decided to join OEA’s Educator Empowerment Academy, the instant connection and rapport she felt with the Western Regional team of BIPOC educators was palpable. After a year of participating in the Academy, she opted to step up as an Empowerment Coach, helping guide other BIPOC teachers in the journey to create and deepen connections within their own districts. The support she’s felt as she’s moved into this work has been vital — especially given the recent racial tensions that have escalated in Albany over the last few months. In early August, the Greater Albany School Board’s incoming school board members (all white men) abruptly fired equity-champion Melissa Goff from her position as District Superintendent, citing “different values and divisiveness.” It was an apparent move to limit the District’s focus on equity, and in the months since, has put a spotlight on the racism that exists in Albany’s school leadership.

Norina Andina is currently an ELD teacher at Sunrise Elementary in Albany. About half of her students are Latino; she thrives in helping her students find ways to celebrate, connect with and honor their cultural backgrounds through her teaching, including the use of music, cultural dress and art.

Through it all, Andina seems to have maintained a sense of calm and focus, especially during a time that could have put an added emotional burden on her as one of the few teachers of color in the district. She credits the President of her local association for providing additional support and reassurance during this tumultuous season — but, mostly, it’s been the connections with other BIPOC teachers, particularly in affinity space, that have reignited her love of teaching and helped her work through those common feelings of burnout.

If our goal is to funnel more BIPOC students into the teacher pipeline, we have to show them that the profession is primed to support their success. This includes making sure the curriculum they receive during their K-12 years is culturally responsive; it includes deepening the connections our public schools have with ethnically diverse communities; it means ensuring students of color have teachers who look like them; it requires us to rethink how we recruit for and make teacher prep programs feasible for first-generation college students. And, once they’re in the profession, district and union leadership can and must prioritize a teacher’s social, emotional, and professional journey through instructional coaching, mentorship, and affinity space with other BIPOC staff.

As she moves on from her title as Oregon’s Teacher of the Year, Butler- Hooton is committed to supporting Oregon educators in creating space for a more representative teaching demographic. “Doing equity work can be lonely — but as we become more equitable, anti-racist and culturally responsive teachers, we begin to understand and acknowledge our own bias and lived experiences,” she says.

“I think our time is now to really address the racial climate and to empower the next generation of teachers, specifically BIPOC teachers, to lead this change.”