Pete Hernberg became the President of Blue Mountain Community College Faculty Association just weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down campuses across the state in March 2020. The bargaining team had just reached a contract agreement with the college, and Hernberg says he didn’t anticipate any major labor issues on the horizon. He never could have expected the year that would follow.

Classes shifted abruptly into online formats the week of March 16, which happened to be finals week for Blue Mountain students and educators. During Spring Break, instructors scrambled to adapt their courses to a distance-learning model. Everyone at the college felt the strain of such a hasty change to their daily routines, but none more than the members of the Corrections Education Program. As prisons statewide became hotbeds for COVID-19 outbreaks, community-based programs were placed on hold. Corrections instructors were effectively locked out of their jobs for several months. Fortunately, Blue Mountain faculty have strong retrenchment language in their contracts, which allowed them to be paid during this involuntary shutdown of their program. It was when they returned to work months later, at the height of the pandemic, that things took a troubling turn.

In August, Blue Mountain Community College administrators alerted Hernberg that meetings between the college and the Oregon Department of Corrections (DOC) had begun regarding the renewal of their contract to provide Adult Basic Education (ABE) and GED courses to three of the prisons in the region. Six Oregon community colleges have been contracted to provide adult education programs to Oregon’s 14 correctional institutions for over 20 years, and much longer in some cases. Blue Mountain has been working with adults in custody (AIC) at the Eastern Oregon Correctional Facility since 1985.

“We knew that the contract was due to expire at the end of January 2021, but the last couple of negotiations had been pretty straightforward, so we sort of expected it would be a relatively simple contract renewal,” Hernberg says.

UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT

On September 30, DOC Director Colette Peters issued a letter to the Oregon Community College Association (OCCA), detailing the new requirements for the colleges to continue providing education services to Oregon’s correctional facilities. The agency was facing budget cuts as a result of the pandemic, and the $16.4 million spent each biennium to contract the work to professional educators was too great a cost. In the letter, Peters called out the agency’s need to standardize education programming hours for all colleges, offer year-round education, and significant program budget cuts. If the requirements were not met in their entirety, the DOC had a plan in place to bring ABE and GED programs in-house, at a potential cost savings of $3.4 million. In the letter, Peters states that “the requirements are not negotiable. We are not looking at this as the start of negotiations but as a final offer to the colleges before DOC moves forward with bringing education in house.”

The approach was a departure from the collaborative process that college leaders had come to expect from their contract negotiations with the DOC. Hernberg says that the requirements were never designed to be met by colleges. “The claim that they wanted to have a consistent program across the state, on its face, seems totally reasonable, but it just wasn't practical. Once you start to understand how these prisons work you realize that each one of these institutions runs very differently. You may have high security environments where you have very strict limits in terms of the extent to which the adults in custody can even be in the same room with one another, versus other environments where they have a lot more freedom,” he says.

The DOC’s budget plan showed another motive for pulling the plug on their contracts with the colleges. With expected future budget cuts on the horizon, the agency was focused on “establishing positions for qualified staff to go into in the event their positions are impacted by future layoffs.” OCCA leaders expressed concern with the idea that prison guards were considered “qualified” to provide educational services to AIC. They also claimed that the increasingly unreasonable demands of the DOC demonstrated no genuine desire on their part to negotiate a new contract with the colleges, yet they submitted a proposal that made substantial concessions toward meeting the DOC’s requirements. The proposal was rejected on October 16. It was clear that the decision to take these programs in-house had been made before any discussions on the matter had ever happened.

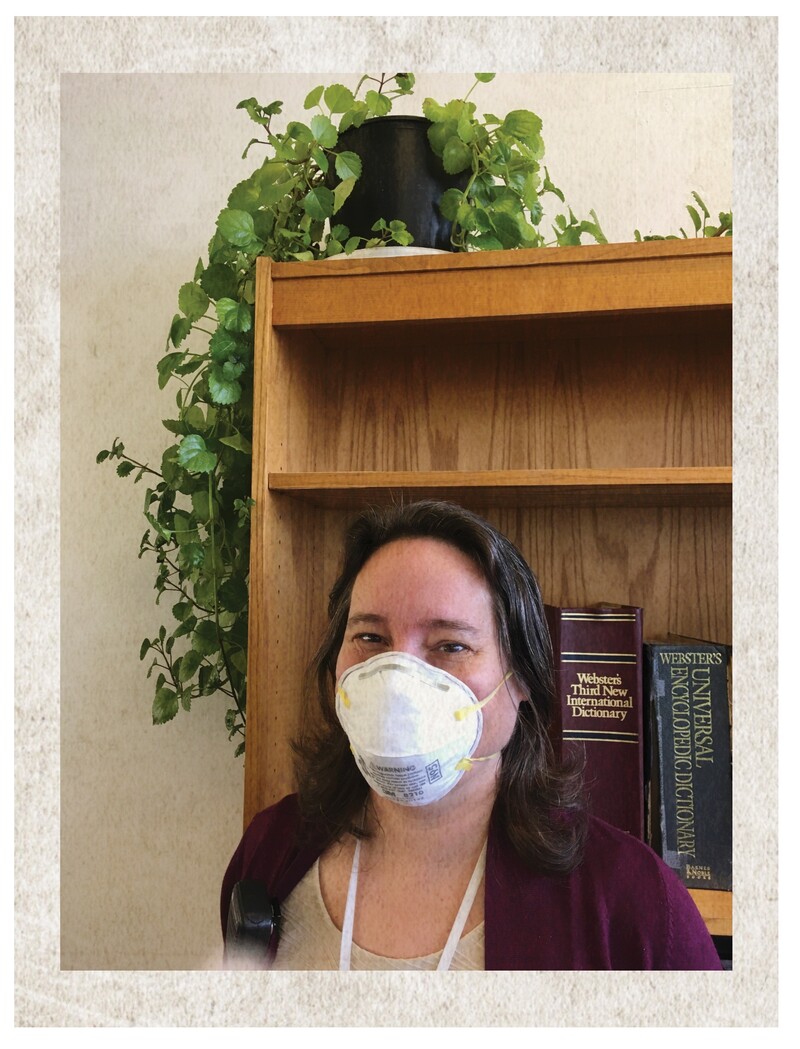

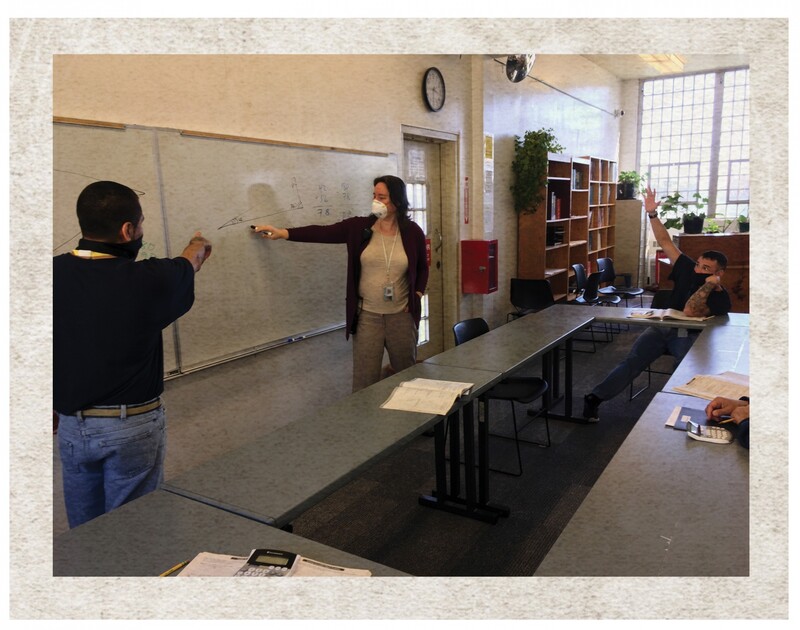

Corrections instructor Heather Goldblatt knows how important Corrections programs are to her at-risk students.

SHUCKING BEST PRACTICES

Heather Goldblatt found out in October that she would not have a job after January 31, 2021. She had been a corrections instructor at Chemeketa Community College for four years, and the news came as a devastating blow. Goldblatt’s career as an educator has been spent working in alternative education, and she knows how important these programs are to at-risk students, especially adults.

“I have a heart to work with underserved people and I know from experience that sometimes when someone is incarcerated, they're really hungry for change and they’re receptive. I feel like a lot of meaningful work can happen in those programs because you know they're going to show up and you can work to build those relationships,” she says.

She knew that any ABE or GED program provided by the DOC would not provide the same level of educational support that can be offered by professional educators. Oregon is consistently in the top five states nationwide for the number of GED completions, in no small part thanks to the six correctional education programs offered by community colleges around the state. Around 70 correctional educators are responsible for upwards of 20 percent of all GEDs earned in Oregon. Goldblatt saw the DOC’s move as a major regression for an agency that is already in need of serious reform.

“When community-based professional educators come in, we bring best practices. We bring equitable approaches, we bring anti-racist practices, and these students aren’t going to get that from an institution that is so antiquated and hierarchical. We need more community-based programs in prisons, not fewer.”

Heather Goldblatt works with students in the adult corrections program at Chemeketa Community College.

ALL HANDS ON DECK

The loss of the DOC contract would result in layoffs for 13 full-time and 3 part-time corrections instructors at Blue Mountain Community College, over 20 percent of the faculty association. As President, Hernberg took swift action on behalf of his members, crediting the open relationship between the union and institutional leadership for the ability to move quickly. “Because they were letting us know what was happening right away, that made it possible to mobilize our advocacy so quickly,” he says.

His first move was to notify OEA. He contacted his UniServ consultant, Brett Nair, who immediately sounded the alarm with OEA’s Government Relations team. Louis DeSitter, an OEA lobbyist, worked quickly to create an action plan that Hernberg could use to mobilize his membership. DeSitter also began making calls to schedule Hernberg and other community college members from around the state to give public testimony before the Senate Committee for Education, as well as the Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC).

Hernberg began sending weekly emails urging members to write to their local legislators and the governor, to sign petitions, to provide written testimony at hearings, and engage in any kind of advocacy on this issue that they could. He says that his members and the entire Blue Mountain Community College staff showed unwavering support of their colleagues, noting that some of the correction program’s most vocal advocates were the classified union members.

“I've never in my life written to a politician and I found myself writing to them constantly,” he says, “Some of our members actually developed real relationships with these leaders as well.”

With growing concern for the fate of her students, and her own job on the line, Goldblatt went to her union for help. Chemeketa’s faculty association leaders were aware of the situation, but didn't have the granular knowledge about the corrections programs to counter the false arguments being made by the DOC. Goldblatt was well-versed in the particulars, so she became a major resource for Chemeketa’s advocacy efforts. She did her part by writing letters to her local lawmakers and to the members of the Senate and House Education Committee. She was surprised to find that they actually sent responses. “They thanked me and said that they knew about the situation and that they were totally supportive,” she says.

Meanwhile, Hernberg was preparing to give public testimony before the HECC. When the day finally came, he learned that he had an ally on the commission. Enrique Farrera, another OEA member who works at Chemeketa Community College, is a non-voting member of HECC.

“I don't know if you've ever given public testimony, but the normal effect is that the committee just listens politely and nods and then they move on and nothing happens,” says Hernberg. That wasn’t going to be the case this time. With Farrera's support, the HECC took action by contacting the Governor’s office as well as the DOC to demand that the lines of communication between the agency and the colleges be resumed.

The issue caught the attention of Senator Bill Hansell (R-Athena), who penned a letter to Governor Kate Brown urging her to step in to salvage the relationship between the DOC and the OCCA, and Senator Michael Dembrow (D-Portland), once a professor at Portland Community College and who now serves as the chair of the Senate Committee on Education. The two lawmakers were able to organize a meeting between the agency and college leaders, finally creating a path to negotiation in what had become an inhospitable situation.

“I have a heart to work with underserved people and I know from experience that sometimes when someone is incarcerated, they're really hungry for change and they’re receptive. I feel like a lot of meaningful work can happen in those programs because you know they're going to show up and you can work to build those relationships."

— Heather Goldblatt, corrections instructor at Chemeketa Community College

MOVING FORWARD

In mid-November, the two parties reached a tentative agreement. The colleges conceded to many of the DOC’s requirements, including substantial cuts to their budgets and increased service hours.

Blue Mountain Community College took the biggest hit. Between 40-50% of their program budget was cut. In the past, their contract with the DOC has been a significant chunk of the agency’s budget for adult basic education programs, but the college also provides a much wider scope of services than the other institutions in the OCCA. AIC who are under the age of 21 are protected by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which means that prisons are required to provide special education to those who are eligible. BMCC has been providing a full range of special education diagnostics and services to the three prisons it serves. The loss of nearly half of their budget would mean that the college would either have to lay off most of the correctional education instructors and provide much fewer services or end the program altogether.

Senators Dembrow and Hansell stepped in to make sure that didn’t happen. Included in the budget reconciliation bill passed on April 8, 2021 (HB 5042), was an additional $542,000 for BMCC’s Corrections Education Program. “BMCC is doing fantastic work to help those in our correctional institutions gain the life skills they need to reduce recidivism and transition back into the workforce,” Hansell says, “BMCC is a value to our community and this is yet another example of an important program they provide. Working with Sen. Michael Dembrow I am very pleased to have secured funding for their Corrections Education Program.”

The funding wasn’t quite enough to save the jobs of all program staff. “In the end we lost our three part time faculty members and one full-time faculty member, but the risk that we were facing was that the whole program would go away and everyone would be laid off,’ says Hernberg. While it wasn’t an ideal solution, he says that the mitigated losses are still worth celebrating.

Though Goldblatt is grateful that her job is safe, she knows that the fight isn’t over. “It’s obviously great that we get to keep our program running, but the DOC is totally laying groundwork so that at the end of our new two-year contract, they're going to be ready. The work is not done,” she says.

Hernberg says he will be ready to fight again, knowing he has the support of his membership and the full weight of OEA behind him. “As hard as it was to go through the whole process, this is why we have a union. When people's jobs are on the line and you're fighting to preserve your members’ livelihoods, you know that you're right where you're supposed to be.”