EVERY DAY during the five-week 2018 Legislative Session, lawmakers heard from OEA members. Teachers, instructional assistants, counselors, and other staff recounted stories of their children. They described the disrupted learning crisis in caring, heartfelt terms. The pain of students whose mental health needs were going unmet, whose class sizes were bursting at the seams, whose social-emotional challenges were matched by academic struggles, and whose services and electives had been penciled out due to underfunding — all of it was brought into sharp focus and laid at the feet of Oregon’s 79th Legislative Assembly.

In response, Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem) and Speaker of the House Tina Kotek (D-Portland) created the Joint Committee on Student Success (JCSS) and tasked this bicameral, bipartisan group with a yearlong project to better understand the condition of our public schools and to determine how to help. From March to October of that year, this group traveled 2700 miles across the state, visited 77 schools, and collected ideas. They met with key leaders, such as the Quality Education Commission and changemakers in other states, to hear about educational best practices. They listened to students, parents, educators, business leaders, and community voices. They heard over and over a singular theme: Oregon’s 30-year disinvestment in its public education system had laid the groundwork for an inter-related series of academic and student health crises and poor prospects for universal student success.

In December, JCSS members compiled a long list of possible initiatives to address this fundamental problem, complete with rough estimates of cost. They continued to meet in subcommittees and as a full committee in the 2019 Legislative Session, spending two evenings a week hearing testimony, refining ideas, and developing a revenue plan to pay for these ambitious goals.

Throughout the summer and fall of 2018, another group formed to explore paths for raising corporate revenue. The Coalition for the Common Good (CCG), composed of representatives from key unions and businesses, identified various tax approaches and conducted research. CCG’s goal was to provide input to revenue legislators and to help ensure a plan’s enactment in 2019. OEA was a founding member of this effort.

Meanwhile, a small group of education advocates, led by Gov. Kate Brown’s Education Policy Adviser, Lindsey Capps, met quietly for two months to build a student investment fund that would incorporate the highest-priority ideas of educators, parents, and policymakers to create the schools our students deserve. This group, which included representatives from OEA, the school boards association (OSBA), administrators’ group (COSA), and Stand for Children, patterned its plan off the successful, educator-built “School Improvement Fund”. That plan, though funded just twice, had piloted successful extra investments through non-competitive grants. It offered an approach that balanced the Legislature’s interest in earmarking the use of new resources with the crucial principles of student-centered programming, local control, district flexibility, and community involvement.

The student investment fund (SIF) group envisioned the targeting of most resources to K-12 through four “buckets” of related uses: class size and caseload reduction; well-rounded education (art, music, PE, CTE, librarians, and more); more time (broadly defined, such as before- and- after-school programs, a longer day or year, summer school, and technology upgrades to create more computer lab time); and student health and safety (more school nurses, wraparound services, trauma-informed practices, and mental health supports). The SIF group also envisioned a special fund for the 10 districts with the most severely and chronically challenged students.

JCSS Co-chairs Sen. Arnie Roblan and Rep. Barbara Smith Warner, as well as a few of their JCSS colleagues, met with this group to hear its vision. They adapted this plan, adding other ideas from pending legislation, JCSS member priorities, and the revenue plan to create what is now known as the Student Success Act. Blending these streams, HB 3427 was born.

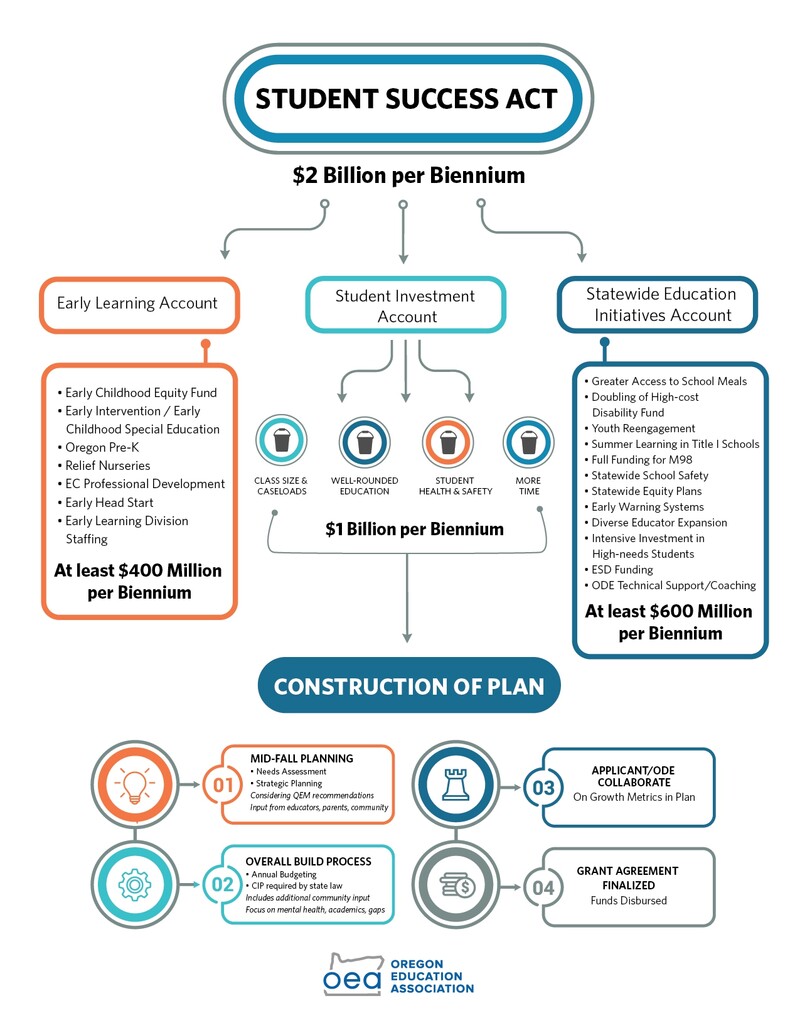

The Student Success Act is composed of three investment streams plus the revenue plan. The first stream, the SIF group’s Student Investment Fund, would receive at least 50 percent of the $2 billion in new biennial resources. A second stream, receiving at least 20 percent of the Fund, would be dedicated to various early learning strategies, such as Oregon Pre-K, relief nurseries, early intervention/early special education, and a new early childhood equity program. The final stream of funds would use up to 30 percent to underwrite a list of statewide education initiatives in K-12, such as the expansion of access to school meals for Oregon’s school children — more than half of whom are from low-income households. The latter category could decline over time as infrastructure and administrative investment needs wane. These funds will then shift to the Student Investment and Early Education accounts.

Because Oregon is near the bottom in the share of taxes paid by businesses operating in the state, the revenue plan focuses on correcting this imbalance to generate the Student Success Act resources. A new corporate activities tax, modified at the request of industry leaders, imposes a small, .57 percent tax on gross receipts after allowing a 35 percent deduction for labor or other costs. Just 40,000 of 460,000 businesses will be subject to the tax, which protects small business by exempting the first $1 million of taxable receipts and also exempts food, fuel, and hospital sectors. Because some economists predict that this tax might slightly increase prices, all Oregonians are also given a .25 percent personal income tax cut in the Student Success Act. Small businesses also pay taxes through the personal income tax side of the ledger, so this cut represents a second way small business is advantaged under the Act.

INVESTING IN OUR STUDENTS

The heart of HB 3427 is the $1 billion grant account, Student Investment Account (SIA). Its purpose is to meet students’ mental or behavioral health needs, to increase academic achievement, and to reduce disparities among demographic groups. Money is allocated primarily to school districts based on each district’s student counts (ADMw in the school funding formula) but doubling the weight for poverty. Virtual charter schools are not included in the program. A brick-and-mortar charter school, on the other hand, may apply for its share of the resource if it serves at least 35 percent low-income population, disabled students, or students of color, and if its demographic density exceeds that of the resident school district. Estimates are that just 10 of Oregon’s 127 charter schools would be eligible to apply. The rest would be offered participation under their sponsoring school districts’ plan if the district chooses and if the charter schools agree. They must comply with all elements of the district-led plan if they participate.

Accountability and transparency are embedded in the SIA. Though all districts will receive their share of the Fund if they complete an application, they must agree to involve educators and community stakeholders in the planning. First, a district must have a strategic plan and conduct a needs assessment (also required under the federal ESSA law). Then, based on needs identification, an applicant must align its ESSA-required continuous improvement plan (CIP), its annual budget, the recommendations of the Quality Education Model, and educator and parent involvement to develop a plan reflective of all these inputs. If a district needs technical assistance with any of these steps, the Department of Education (ODE) will be there to help, but not direct. Next, the applicant and ODE will collaborate to establish reasonable growth targets, based on state and optional local metrics for measuring success. The state indicators are third-grade reading, chronic absenteeism rates, ninth-grade on-track, and graduation (diploma or GED). Local measures, such as a percentage decrease in room clears or class-size reduction in K-3 to research-guided levels, might also be added. When fully calibrated, the plan is then presented to the local governing board for public comment, and then, ODE and the applicant sign an agreement and checks are cut. The plans are for four years, with application renewal at the two-year mark, except for the startup period in which plans will be three-year documents with a one-year reapplication. ESDs may also apply, using their funds in support of component districts.

The Student Success Act’s accountability provisions is one area OEA worked diligently to soften. Gone from the original concept are expensive annual performance audits and punitive responses to stalled student growth. Instead, ODE will focus on technical support, coaching, and collaborative approaches that begin with an analysis of the reasons for any “outcome” concerns. Standard annual financial audits will include these funds, and districts are asked to review their progress with students each year.

Time for teacher collaboration, professional development, and other proven strategies are embedded in the Act’s approach. For students, an emphasis on meaningful equity practices and culturally relevant strategies are designed to ensure that all students have the chance to achieve their dreams. The entire Student Success Act will continue biennium after biennium, supplementing the un-earmarked State School Fund base budget for a total state investment that comes within 97 percent of the Quality Education Model’s estimate of school funding adequacy.

HOW DID WE GET TO YES?

Oregon’s long march of education disinvestment followed on the heels of several major changes to its revenue system. Not only did the mostly property-tax-fed school system prior to 1990 fall siege to two limitation measures (Measure 5 in 1990 and Measure 50 in 1997), but the corporate income-tax share of the General Fund also dropped from 18 percent in 1973 to just 6 percent today.

Shouldering most of the load for schools was the personal income tax, paid by individuals and small businesses. When the economy falters, this personal income tax resource vacillates, making school funding not only insufficient, but unstable. Over the years, OEA has worked to establish reserve accounts to hedge against that instability, as well as to bolster overall General Fund resources by recommending cuts to preferential tax breaks and by sponsoring tax transparency and rate increase initiatives.

In 2010, OEA helped to sustain two small tax increases by the legislature that were challenged on the ballot (Measures 66 and 67). In 2012, the association sought and won redirection of the corporate kicker to K-12 education. These incremental gains, however, were not enough. In 2016, OEA and its allies pursued Measure 97, a gross-receipts tax that would have raised $6 billion for schools and other vital state services. As with the Student Success Act, education’s share of the revenue would have been $2 billion per two-year budget period. More than $20 million in corporate funds were deployed to defeat this plan. Opponents argued that the measure constituted an “open checkbook” because the funds were not dedicated to education. Undaunted, OEA members pressed on. In 2018, OEA was part of a coalition that successfully defended the health-care provider tax, also challenged by voter referendum.

The association also knew that taxpayers had voted in bond and local-option levy elections all over the state to tax themselves to pay for school capital projects and operations. It was this history, along with inspiration from the growing national Red for Ed movement, that formed the basis for OEA’s push for the Student Success Act.

Fast-forward to February 18, 2019, when 5,000 educators and parents, clad in red tshirts, descended upon the state capitol in Salem to demand adequate school funding, once and for all. This historic show of support was followed by more action at OEA’s March 25 lobby day.

On May 8, history was made once again when educators launched a statewide day of action, walking out and closing schools across the state, conducing teach-ins, and drawing national attention.

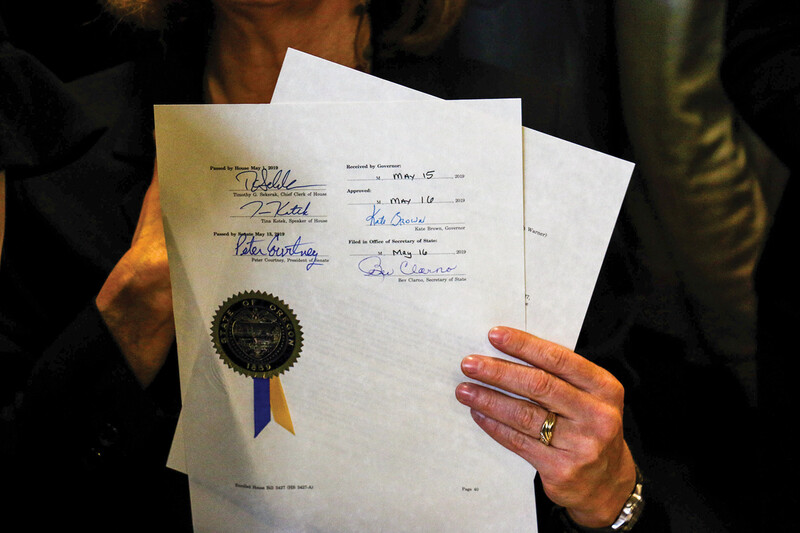

On May 13, 2019, after Republicans walked out for five days in opposition, the Student Success Act was passed by the Oregon Senate, having passed the House on a 35-25 vote a week before. Gov. Brown signed the bill on May 16, with a ceremonial signing on May 20. Oregon’s Constitution requires that revenue-raising legislation may not be enacted until the 91st day after adjournment of the legislative session, to give opponents time to mount a referendum challenge. One business group, Oregon Manufacturing and Industry, announced its intent to circulate petitions challenging the measure, but in mid-July, that group announced suspension of its efforts. Without a referendum, the Student Success Act officially becomes law on January 1, 2020, and education districts will begin to receive resources July 1, 2020.