She was in the seventh grade.

Her teacher had told her they would be studying African American history in class, and she was thrilled. For the first time in her schooling up to this point, she’d see her own ancestral history on the pages of her textbooks.

The entire unit ended up being one film about slaves coming over to this continent from Africa. Her classmates kept looking back at her and then at the screen, whispering.

“I thought, 'this is it?' It made it clear to me that the contributions of my racial group were not going to be taught. They were not spoken of. I became very angry. I used to love school, and then I didn’t really love it anymore,” Jennifer Scurlock remembers.

It’s a different story now for Scurlock, who teaches Language Arts at Churchill High School in Eugene. She opens the school year with a personal narrative project on overcoming obstacles, which each student presents in front of the class. There are often tears in this vulnerable space. “My goal is to create a safe classroom environment so that when we talk about racism, or sexism, or socioeconomic inequities, they can really learn from and listen to each other,” she says.

She knows that she has to own some of that process, too. “Do I have to put myself on the line and pour my own heart out? Yes, I do. Do I get emotional? Yes, I do. But does it inspire their voice? Yes, and so it is well worth it,” Scurlock reflects.

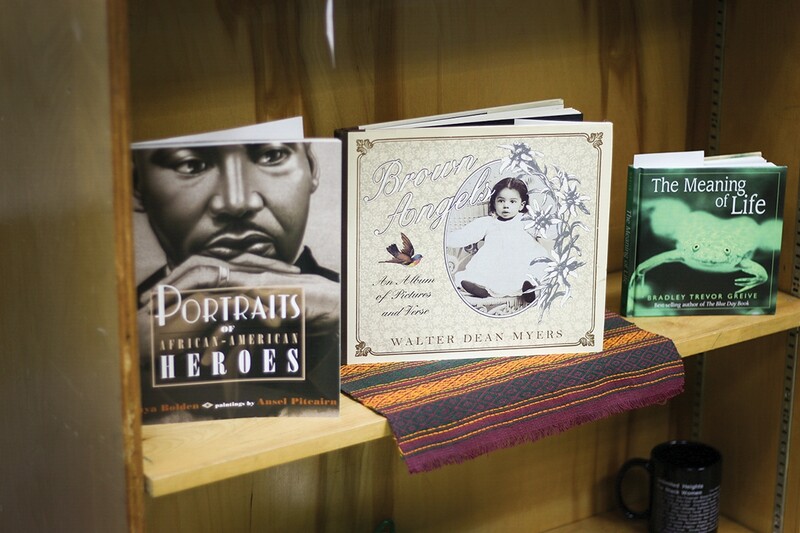

Around Scurlock’s classroom hang cultural artifacts; on bookshelves, you’ll find texts featuring authors of every ethnicity, telling the stories of each and every racial group represented in her classroom, and then some.

Scurlock, who was recently appointed an NEA Director to represent OEA members at the national level and is part of OEA’s Ethnic Minority Affairs Committee, can talk about systems-level equity work.

If you ask her, she’ll tell you how our union can more strategically address institutional racism for our students and staff of color. But despite her state and national level experiences, for Scurlock, one thing remains abundantly clear: creating safer, more welcoming spaces where all students can thrive will always start where the heart of a school beats: in the classroom.

Addressing a Real and Rampant Problem

One doesn’t need to be told a slew of statistics to know that systemic racism is alive and well in public schools today. Nevertheless, the statistics paint a pretty clear picture, starting as early as preschool. Last year, NPR reported that African American preschoolers make up just 18 percent of the preschool population but represent nearly half of all out-of-school suspensions.

By the time students of color enter K-12, the rates have climbed. Black students make up almost 40 percent of all school expulsions, and more than two-thirds of students referred to police from schools are either Latino or African American, according to the Department of Education. By the same study, black children are three times more likely to be suspended than white children.

"Education and history must focus on the positive contributions of every racial group," Scurlock says, a value that is reflected on the walls of her classroom. "If we do not do that, we are feeding into systemic racism."

By the time senior year rolls around, only 50 percent of all black students, 51 percent of Native American students and 53 percent of all Latino students will graduate from high school (with the rates for solely male students nearly 10 percentage points worse, respectively), according to a report released by the Urban Institute and the Civil Rights Project at Harvard called “Losing Our Future: How Minority Youth Are Being Left Behind by the Graduation Rate Crisis.”

The question, of course, isn’t whether or not institutional racism exists in our schools. It painfully and clearly does.

This past year, in particular, has been an uphill fight for education’s social justice movement. From a national standpoint, Donald Trump’s divisive bid for the presidency has created what many educators are calling the “Trump Effect.” Over the course of his candidacy, Trump has spoken of deporting millions of Latino immigrants, building a wall between the United States and Mexico, banning Muslim immigrants and even killing the families of Islamist terrorists.

"Do I have to put myself on the line and pour my own heart out? Yes, I do. Do I get emotional? Yes, I do. But does it inspire their voice? Yes, and so it is well worth it."

— Jennifer Scurlock

This past year, the Southern Poverty Law Center conducted an online survey of approximately 2,000 K-12 teachers and found that respondents noted “an increase in bullying, harassment and intimidation of students whose races, religions or nationalities have been the verbal targets of candidates on the campaign trail," according to their report “The Trump Effect: The Impact of the Presidential Campaign on Our Nation’s Schools.”

Over two-thirds (67 percent) of educators reported that young people in their schools—most often immigrants, children of immigrants, Muslims, African Americans and other students of color—had expressed concern about what might happen to them or their families after the election.

Spurred by a passion for equity, by personal experience, by the often-unfathomable times we’re living in and the national, negative rhetoric around race that has become so pervasive — educators are finding their niche in bringing to light the issues and forging their own paths toward undoing oppression.

"The purpose of understanding how institutionalized racism, or sexism, or any of the ‘isms’ work, is not to create the victim story or elevate the victim story, but to create a transformation story where our students are aware of the circumstances of their lives, AND they have the tools to change."

— Leah Dunbar

Elevating the Discussion

Born just 13 minutes apart, identical twin sisters Leah and Rena Dunbar have deep understanding for what it means to be on the outside of the institution. “I almost feel like we are tri-racial: our black background, our white background, and our multiracial background. Because of that, we’ve been negotiating a lot of different racial spaces and have experienced a lot of ‘othering’ throughout our lives. We had no space that was truly the tri-racial space that was just ours, except with each other,” Rena says.

Their parents were both educators in Fort Wayne, Ind., but lost their jobs in the 1960s because they were a mixed-race couple. “They were trailblazers in a lot of ways because we were a mixed family. I think that being educational activists is in our DNA because of who our parents are,” says Leah.

Eventually, the sisters’ inextricably linked paths led them both to Eugene, Ore., where they student-taught in the same classroom at Churchill High School, three years apart. Their mentor teacher, Diana Granberry, was also a Midwest transplant and civil rights activist who had biracial children. “She was our educational mother — she provided an educational home for so many of her students at Churchill. I really believe that she waited until somebody came along who could carry the torch and take care of vulnerable students, particularly students of color,” says Leah. Rena gives similar credit to her mentor at South Eugene High School, Sally Lowe.

The torchbearers would, unsurprisingly, become the Dunbar sisters. Sixteen years later, Leah is still teaching in the same classroom where she spent her early years as a student teacher, and Rena teaches at the Early College & Career Options (ECCO) High School on the Lane Community College campus.

“It’s interesting that we both had these mentor teachers who would not retire until they knew that there was somebody to take care of what they called the ‘sleeping giants.’ But I feel like it’s the institution that’s really sleeping. Hopefully, we’re doing our part to wake the institution up,” says Rena.

Together, the sisters have launched a Courageous Conversations program in Eugene 4J, a class offered in four of Eugene’s area high schools where students explore institutionalized racism and internalized oppression, within the vocabulary of equity, and elevate that discussion in other spaces and other classrooms.

"We’re trying to support other teachers in being comfortable of letting go of authority — instead, letting students

have their own authority over their voice and their own sovereignty within the classroom. It is really challenging."

— Rena Dunbar

Through open, meaningful dialogue with one another (each student is required to speak at least once every single day), students begin to understand the “cultural backpack” they come into the room with (as Rena describes it), and how they can begin to unpack it. “It’s process over product, because we’re creating the knowledge along with our students. We’re not in charge. That can be pretty scary because it’s very unpredictable,” Rena says. “We’re trying to support other teachers in being comfortable of letting go of authority — instead, letting students have their own authority over their voice and their own sovereignty within the classroom. It is really challenging.”

The first trimester of the year-long course opens with an Ethnic Studies 101-type curriculum where students learn the language of social justice. “The purpose of understanding how institutionalized racism, or sexism, or any of the ‘isms’ work, is not to create the victim story or elevate the victim story, but to create a transformation story where our students are aware of the circumstances of their lives, AND they have the tools to change,” Leah says.

Rena adds to that — “We talk a lot about de-colonization. We’ve all been institutionalized and taught a certain narrative. If we don’t do well in math, it’s because we’re not smart, as opposed to asking — 'how have I not been seen? How has my story been left out?'” It’s an especially poignant topic for her students enrolled at the alternative high school at LCC, which was originally created as a junior/senior transitions programs for students marginalized by the system. “Our school exists because of institutionalized marginalization – but we can shift the victimization story. I call my students warriors. They have resisted the system and they are survivors,” Rena says.

The second trimester is focused on mass incarceration; students read “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander and explore the intimate connection between the public education system and the criminal justice system. “There is something so authentic about looking at these systems and reflecting how you fit in to them. You can’t begin to understand what has happened in Baltimore, or what’s happening in Charlotte, or what Ferguson meant, without understanding the impact that generational trauma has on all of us,” Leah says, noting how important the Black Lives Matter movement has been to this course so far.

Students analyze how all aspects of human identity have been socialized to separate us rather than bring us together.

The conversations are extraordinarily powerful, and time and again, the Dunbar sisters are inspired by how well-equipped students are to have them.

“Students can engage in conversations about marginalization and racism in ways that many of their own teachers haven’t even experienced,” Leah says of the predominantly white, middle-class teaching force in Oregon.

“It is the responsibility of the people who would like to interrupt the achievement gap to figure out how to support students in having productive conversations about their lives, justice, identity and democracy. That’s the consciousness-raising of the nation that is being forced by this movement.”

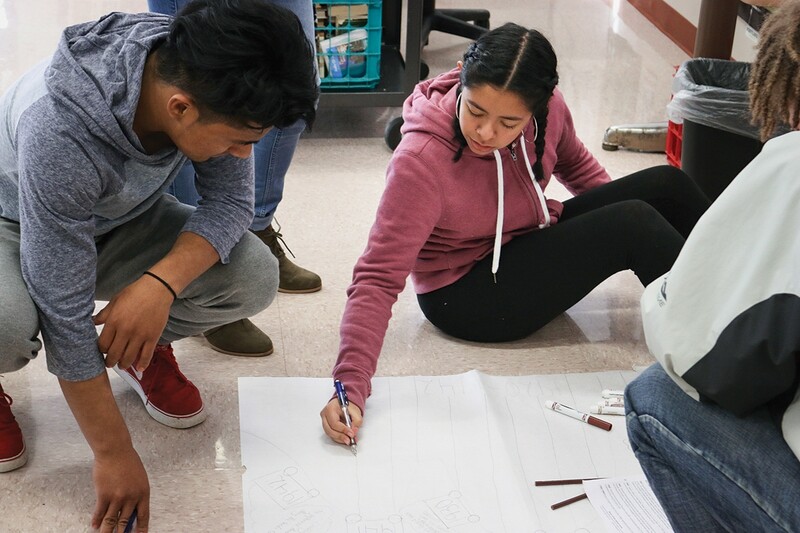

Dawn Nelson engages her students in furthering their analysis on a class project to identify key points in both Oregon and the United State's history that shaped race relations.

Taking a Stand

Last May, the rural community of Forest Grove found itself in the national spotlight of this movement after a racist banner was anonymously hung in the open school foyer at Forest Grove High School. Interestingly, it wasn’t the “Build a Wall” banner, really, that brought media attention to Forest Grove, a school district with a greater percentage of Latino than any other district in Washington, Multnomah and Clackamas counties (approximately 50 percent Hispanic and 50 percent white/non-Hispanic).

The sight of that banner caused student activism to erupt in a way the community hadn’t witnessed before — and people noticed. A week after the incident, hundreds of students walked out of class and down Main Street, joined by community members and other students from five neighboring Washington County schools. After the walkout, students began sharing with the School Board their painful experiences of harassment, microaggressions and bias.

Forest Grove educators listened. On the opening day of teacher in-service this year, Forest Grove Education Association (FGEA) organized a peaceful solidarity march for students and hung positive, affirming signs around the high school to greet students when they returned to the building the following week. FGEA members spent the remainder of the day in professional development focused on equity. “The district has made a commitment to focusing in on equity this year, and as a local association, we too have looked at how we can be better prepared to deal with race-related issues,” says Jeff Matsumoto, co-president of FGEA. “The voice of the union needs to be really clear about this.”

At the 2016 OEA Representative Assembly, delegates made clear their stance on transforming decades-long patterns of systemic inequities in our public schools.

More than 700 members in the room voted to pass a New Business Item that implored OEA to “lead to address institutional racism by: 1) Spotlighting systemic patterns of inequity — racism and educational injustice — that impact our students; and 2) Taking action to enhance access and opportunity for all Oregon students, consistent with the NEA Institutional Racism NBI. OEA will use our collective voice to bring to light the ongoing institutional racism and initiate change to policies, programs, and practices that condone or ignore unequal treatment and hinder student success.”

Matsumoto and his co-president Marcia Camacho look to their fellow teachers for inspiring examples of this work already underway. The need could not be more pressing, especially given the events of

the last year in Forest Grove. “I feel like we are behind in this work already,” says Camacho. “The students are leading and as educators, we’ve been called up short a little bit in terms of what the students are doing. We don’t have the luxury to take a really gradual approach to equity work. The kids need it now.”

“We’re humans, and sometimes our conversations can be a little messy and difficult. But, I want this to be as much as possible a place where they can feel comfortable.”

— Dawn Nelson

Building the Curriculum

When she moved to Forest Grove from the Bay Area five years ago, high school English teacher Dawn Nelson noticed that there was an engagement gap, so to speak, for the Latino students at FGHS. She was eager to make changes in her own curriculum, but because of the recession and tight funding, there wasn’t a lot of wiggle room to introduce anything new. “I wanted [my class] to reflect their backgrounds, their questions and their interests,” Nelson says of her Latino students.

Each year, Nelson would approach her administrators about the idea of adding on a “Culture and Identity” elective course. The course was finally approved this year as a general-ed English 11 course. One of the first assignments was to read a book called Century of the Wind, a brief history of 20th century from the Latin American perspective.

Many of Nelson’s students spoke about how wrong it seemed that they were nearly 18 years old and this was the rst time they’d really been given the opportunity to learn about their own cultural histories. “I nd that, as an English teacher, I focus more on the historical and current events that surround a novel than I do the actual novel. I like to let the kids explore what’s happening in the book, and why it’s relevant to the past and the future and the present,” Nelson says.

Two months in to teaching her first social justice course, Nelson is weathering the normal bumps that come with a new class, new lesson plans, and the start of the school year. “The kids and I are on this journey. It’s very fluid,” she says. Inevitably, not every day goes according to plan. After opening a class with a project about deconstructing stereotypes, Nelson reflected: “We’re humans, and sometimes our conversations can be a little messy and difficult. But, I want this to be as much as possible a place where they can feel comfortable,” she says.

"I feel like we are behind in this work already. The students are leading and as educators, we’ve been called up short a little bit in terms of what the students are doing. We don’t have the luxury to take a really gradual approach to equity work. The kids need it now."

— Marcia Camacho

Fueling the Pipeline

Interestingly, Nelson almost didn’t teach the course for which she so strongly advocated. “I feel this heavy responsibility for this and I want it to go well. But, honestly I didn’t know if, as a white woman, I was the right person to be teaching it,” she says. The reality, as it often is in Oregon, was that the ethnic diversity of the high school’s staff in no way mirrored the diversity of its student population, which left few options for any other teacher to step to the plate.

Statewide, teacher diversity is on a steady but slow climb upwards. The 2014-15 data in ODE’s "Oregon Educator Equity Report" reveal that the number of culturally and linguistically diverse teachers employed in Oregon public schools has increased by 233 staff members since 2011-12 and is currently 9.7 percent of the employed teacher workforce.

Camacho, FGEA’s Co-President and a teacher at Neil Armstrong Middle School, is pushing the district to forge a partnership with Paci c University, the local college in Forest Grove, to provide financial support to students of color interested in pursuing a career in teaching. “We simply do not have enough staff of color at the high school or middle school levels. It’s good at the elementary level in our dual language schools,” she says. “I taught in the [elementary] bilingual program, and there were some very talented future teachers right there in front of me," she says of her former students. "But, we can’t expect them to negotiate the whole college system on their own — it’s so complicated.”

Matsumoto, a fourth grade teacher at Harvey Clark Elementary, has hope such a program will eventually take ight. “We need to look at how we can get those kids into the profession. How we can engage them and say, ‘This is a worthwhile endeavor. You will impact so many lives.' And yet, I don’t think there's an outlet for that yet in Forest Grove, at least that I’m aware of,” he says.

After nearly leaving teaching for good due to ongoing racial microaggressions in her former school, Jennifer Scur- lock has found a new and welcoming home at Churchill High School.

Protecting Our Greatest Resources

Jennifer Scurlock, the Language Arts teacher in Eugene, knows the union has a powerful role in seeing this work through.

It was just two short years ago that Scurlock was on the brink of leaving the teaching profession forever.

In 2013, Scurlock had grown increasingly aware of how many of her students were targeting her with racist comments. She’d walk by a group of kids in the hall and hear the ‘N’ word. The same was happening to her son, Donovan, in his school — he’d hear students make jokes about wearing KKK hoodies in his presence, as an example. When she mentioned the incidences to fellow staff members who were not of color, they brushed it aside — trying to minimize what was happening to her as ‘kids just being kids.’

“I realized I could not stay in a place that either minimalized or ignored the impact of institutional racism. That minimization over a long period of time made me question if I should continue to teach, and even continue to live in Oregon," she remembers, her voice breaking. "How doI raise my kids in a place where they don’t feel safe?”

Scurlock’s darkest days as a teacher and parent ended up becoming a turning point. Eugene Education Association President Tad Shannon knew what Scurlock was going through and invited her to attend an NEA Leadership Conference focused on equity and social justice. He repeatedly checked in with Scurlock and helped her transfer to a new school environment at Churchill, which has made all the difference. “He really wanted to make sure that I knew that OEA — my union — knew I was important,” she says.

And that, right there, is the key. “If the union is truly behind addressing issues of institutional racism, then the union must be present in these conversations. That’s it.

Latino students make up nearly half of the student population at Forest Grove High School and were the driving force behind last year's solidarity actions.

Now is the time for us to be moving these conversations forward,” she says.

One of the keys to changing this culture, Scurlock believes, is a more focused effort on recruiting educators of color to take an active role in the union, just as her local president did for her.

“In order to change the culture, we have to intentionally recruit staff of color to be a part of OEA. We have to be culturally competent and be fearless in doing so. Our call to action must be to defend the rights and worth of our students and educators of color. And if we do not do this, we may unintentionally become part of the problem.”