Schools today are grappling with a plethora of serious issues. While it can be cumbersome to address all of them—and we know educators do their best to do so—schools often have to address the larger “macro” issues before they can adequately tackle the day-to-day, or “micro”, concerns. This year, an art teacher from an alternative high school in Portland has honed in on one of these crucial micro-concerns with the goal of improving school morale, culture, and progress.

Something about the school environment at Fir Ridge Campus wasn’t sitting well with Michelle Colbert, an art teacher at the alternative school in the David Douglas School District. She noticed that students were exhibiting micro-aggressions — defined as direct (but usually unintentional) discrimination against marginalized communities.

Colbert says she noticed students making derogatory statements to each other, and when reprimanded, they would respond that they were simply joking around.

“I thought, you know, there’s a piece to this puzzle that’s missing. I want them to understand that while they think they’re joking, these [statements] can actually have long term, negative effects on their peers.”

This observation compelled Colbert to bring the Micro-Aggression Awareness Project into her classroom, with hope that students would, through metacognition, reflect on their own participation with micro-aggressions and the effect they have on others. The culminating project this Spring resulted in large posters of students pictured holding a sign of a micro-aggression they routinely experience. These posters encircle the highly visible Commons area and are a constant visual reminder of the power of the language we use to speak to one another.

By the end of the unit, many of Colbert’s students were able define micro-aggressions in their own words. One of them, Andrew Charlton, defines micro-aggression as “meaningful words that may not be meaningful to a person that’s saying it, but could be meaningful to the person who it’s being said to.”

Student Sadie Gainer says that for her, many micro-aggressions are assumptions based on what she looks like. Another student, Tatum Wilson, understands that micro-aggressions are not always meant in a hurtful way. “People always say them with the intent to be in conversation but [they] actually hurt somebody’s feelings,” says Wilson. Micro-aggressions are not only spoken words but can be actions as well.

Aleathea St. Hilaire opened up about one experience she had, which highlights the prevalence of behavioral micro-aggressions. She recalls being on the street, hungry, and having to panhandle when a group of men walked by and put three pennies in her hat. “I was hungry that day. I was desperate so I had to do something. That in itself was pretty much a micro-aggression. You put three pennies in my hat and you’re giggling when you’re walking by. What you do can be a micro-aggression,” she says.

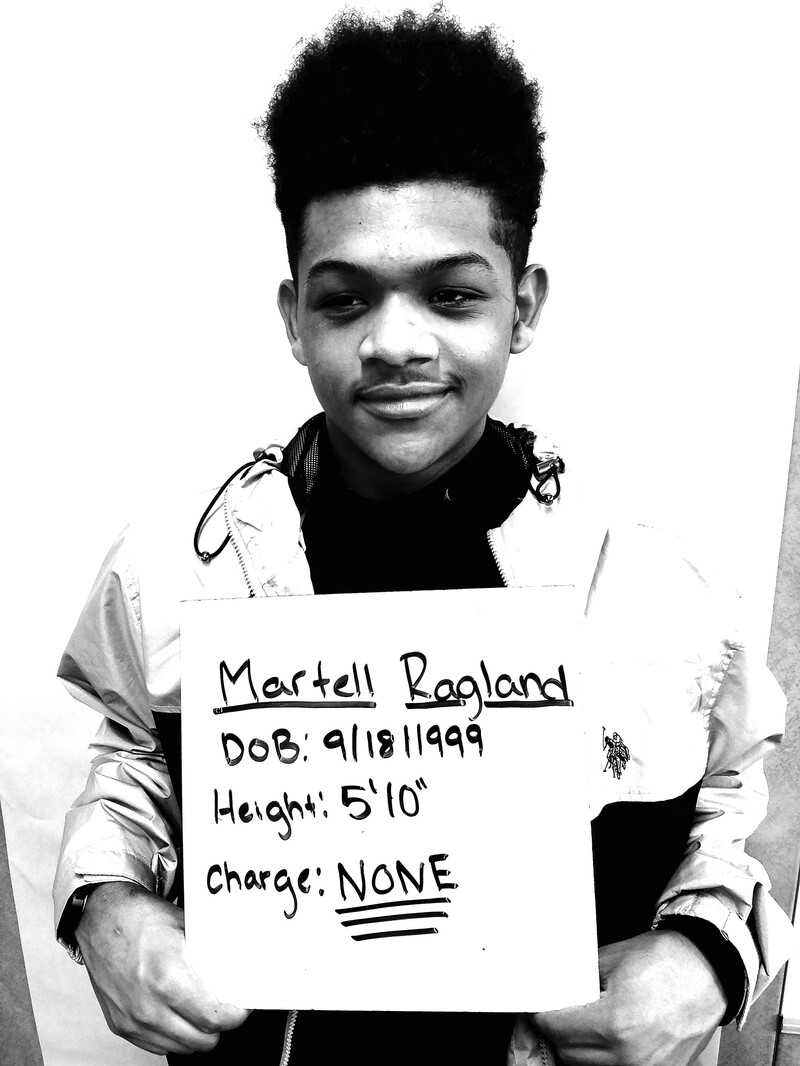

Still, others are uniquely personal or creative. Martell Ragland chose to create a “mug shot” in which he holds a police slate-style sign that includes his name, height, date of birth and criminal charge. For criminal charge, he wrote: “None.” Ragland's micro-aggression addresses the misrepresentation and racial profiling of African American males.

St. Hilaire’s experience is not an anomaly at Fir Ridge. Students are typically behind academically and/or at-risk of dropping out. Almost all have extremely difficult life circumstances. They are no strangers to the harsh reality of insurmountable odds. They bring to the table a genuine reflection of the worlds they experience, thus adding to the success of the project.

Often, schools teach about overt forms of discrimination. There are dozens of “awareness events” like “No One Eats Alone Day”, “The Day of Silence”, Black History Month, and others that aim to bridge our differences through visibility and acknowledgement. The Micro-Aggression Awareness Project is another effort schools can implement to bring the many covert forms of discrimination to light.

Tatum Wilson believes micro-aggression awareness education should be mandatory in schools. She says, “they [schools] always teach you not to bully people, but then they don’t teach how not to bully or what could actually be hurtful.”

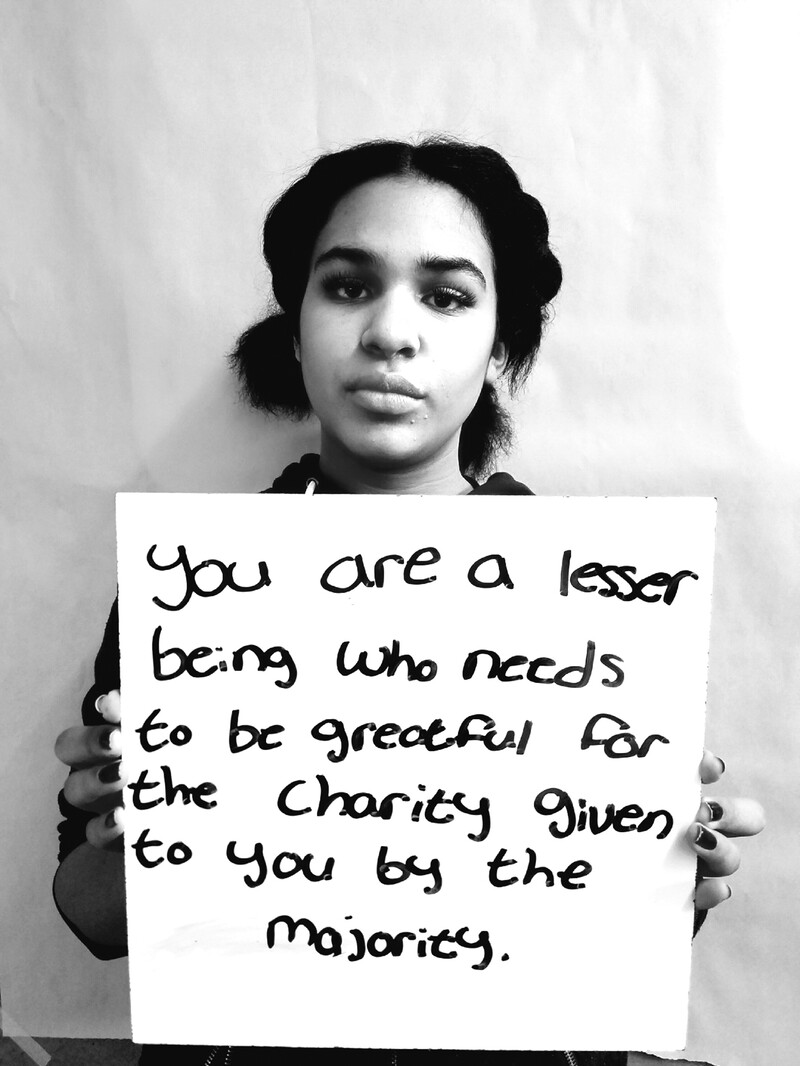

Others are poignantly personal, as in the case of St. Hilaire. She was adopted this year by a loving family, but recounts her experience of being in and out of homes and shelters.

“Anytime I received anything, I always had this thing where people would expect me to be really overwhelmingly grateful for what they’ve done for me.” She says that when she was going through the foster care system, and grieving the absence of her family, foster care providers equated her lack of enthusiasm with ungratefulness. Her micro-aggression example is incredibly personal, but her poster shows a young woman, staring straight ahead, resilient and strong, holding a sign that reads, “You are a lesser being who needs to be [grateful] for the charity given to you by the majority.”

The passivity of micro-aggressions is what makes them so incredibly subtle, yet powerfully engrained in our common conversational patterns. Inevitably, as Fir Ridge’s vice principal La’Shawanta Spears notes, they support systems of discrimination. She says that the project gave her a deeper appreciation for her students and their resilience, and allowed her to reflect on her own practices to ensure that she is looking at the “whole student and not what society depicts them to be.”

One would be hard-pressed to find someone who has never experienced a micro-aggression, which makes this project extremely relatable. In that sense, students and staff are drawn to specific remarks and behaviors that range the gamete, from often-heard and experienced by many, to very personal and individualized experiences. Ramiyah Baker, educator and community partner with Camp Fire, chose “Can I touch your hair?,” which is a common micro-aggression experienced by African Americans.

Art teacher Michelle Colbert chose “That’s pretty good, for a girl,” which is so common it appears to boomerang across all social circles and cultural groups. Colbert says it’s as if “somehow my gender devalued whatever accomplishment I had…nobody could just say, ‘Yeah, you did that pretty good’, but they had to add in the micro-aggression of ‘for a girl’.” Many micro-aggressions spotlight the irreverent thread of society’s views—the underbelly of what we truly think about one another.

Other students chose similar “boomerang” micro-aggressions, such as Tatum Wilson’s, “You like football?”, or Sadie Gainer’s, “Is that your real hair?” Some are related to perceived class like Andrew Charlton’s, “I am not trailer trash.” Others have to do with perceived citizenship, like Christian Gonzalez’s “Just because I’m Mexican doesn’t mean I’m illegal”. Many of these types of micro-aggressions magnify the ways in which we prejudge one another based on characteristics we see.

Others magnify deep-rooted stereotypes that highlight the mountain of work we still have to do as a society to find acceptance and tolerance. For example, consider the following micro-aggressions reported by Fir Ridge students:

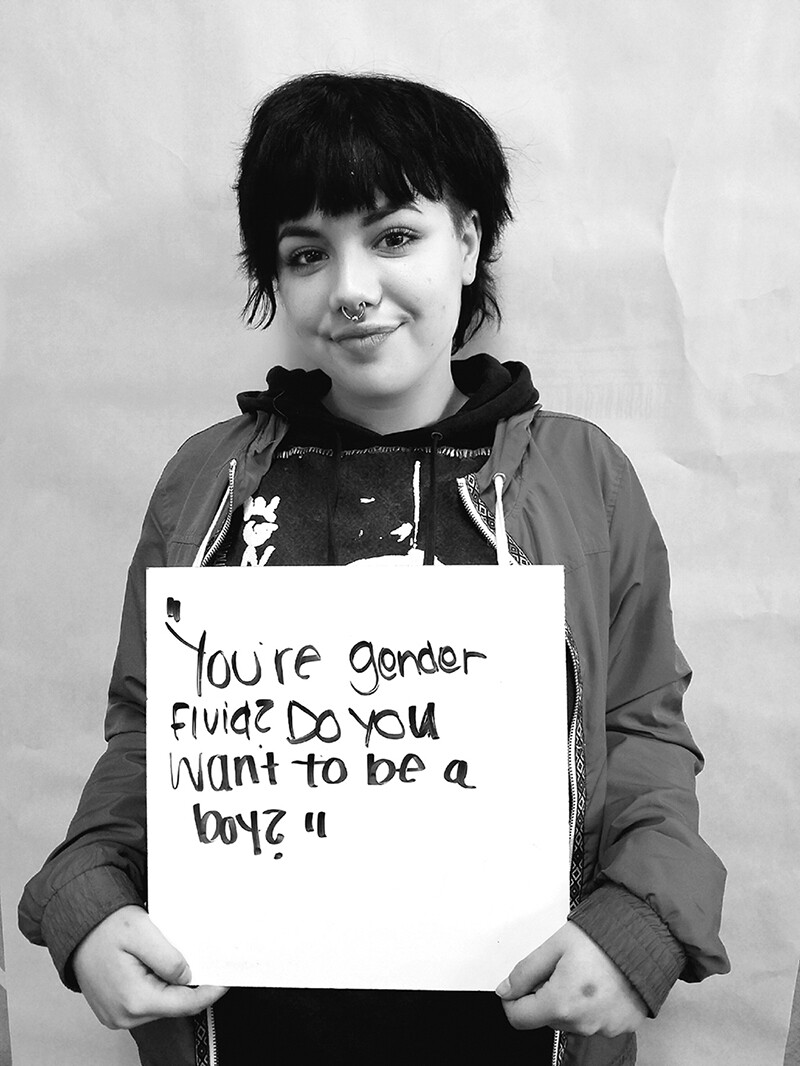

- “You’re gender fluid? Do you want to be a boy?” (Kyran Lindsay)—Demonstrates ignorance regarding gender identity.

- “Actually, I’m not ELD. I’m TAG.” (Kassandra Loya)—Presumes that Hispanic or Latino students are English Language Learners or may struggle with literacy.

- “You look better with your hair down.” (Katelyn)—Reinforces beauty standards for women.

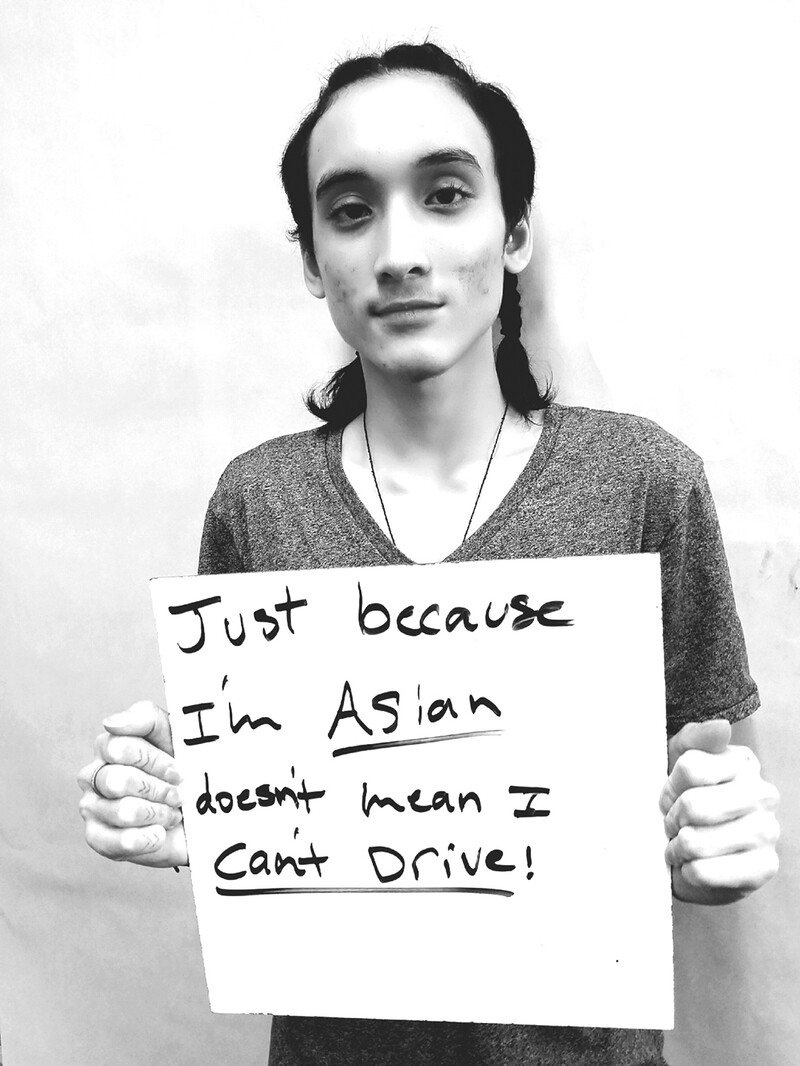

- “Just because I’m Asian doesn’t mean I can’t drive.” (Michael Chau)—Examines specific ethnic and racial stereotypes for Asian Americans.

- “You’re accomplished, for a black girl.” (La’Shawanta Spear)—Observes that there is something remarkable about being black and successful.

This project sheds light on a wide range of experiences with discrimination and generalizations, all of which can easily go uninterrupted. It's begun a necessary, albeit sometimes uncomfortable, dialogue in the school. Martell Ragland says that he has noticed that his classmates have changed the way they interact with each other, even if they don’t realize it. Sadie Gainer acknowledges it’s an uncomfortable topic to talk about, but also that bringing it to the table is a good thing.

As the project supervisor, Michelle Colbert says she likes to think that kids are being more cautious about what they’re saying and really owning their words. She says she hears students calling each other out when they hear micro-aggressions and hopes that this type of behavior will continue.

The posters, which are prominently displayed in the hub of the school, act as a gallery of silent faces beckoning a call to action against a not-so-micro issue, one which Fir Ridge is answering.

Editor's Note: All students' names, photos and personal stories are printed with their permission. Watch a video about their experiences: