Six days.

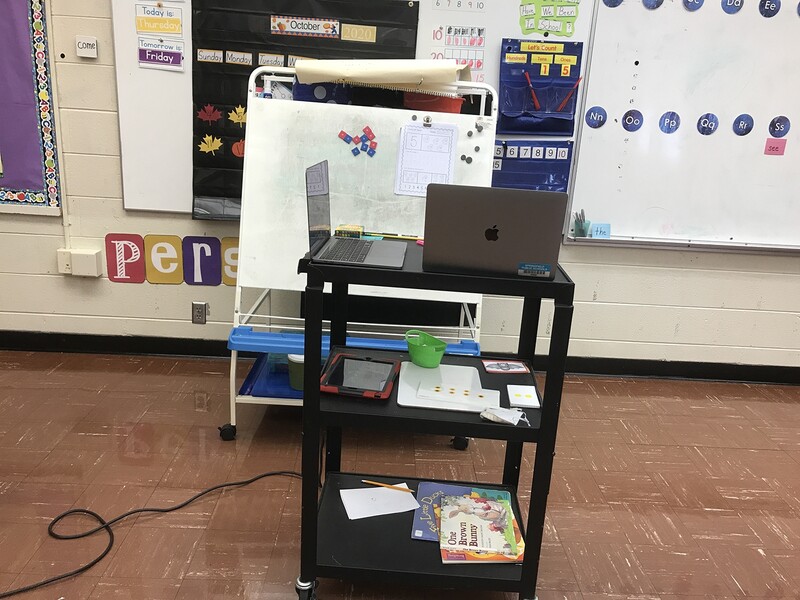

That’s all the time Springfield teacher Anne Goff had with her incoming Kindergarten class face-to-face last month before a COVID-19 surge in Lane County altered everything. Her Kindergarten students had begun their school year in her classroom the week of Sept. 21, and metrics were released the day after school began that showed positivity rates had climbed higher than in-person teaching would have normally allowed. Because the district had already opened, Springfield K-3 classrooms could continue hosting in-person classes until the next round of metrics came out. Not surprisingly, the metrics the following Monday had nearly doubled in positive cases; that evening, teachers were told that the district was returning K-3 students to Comprehensive Distance Learning by the end of the week. The next day, Goff scrambled to get learning packets made for her students, knowing it'd be the last time she'd see them in person for a long while.

Six days of making a face-to-face connection with an eager bunch of five-year-olds. Six days of setting the stage for what is surely going to be a tumultuous year of yoyo-ing between two models of learning that both carry their own hurdles. This abrupt move to close Springfield schools during the second week of school was coupled with devastating levels of unhealthy wildfire smoke that had already forced the district to delay opening schools a week or more. Springfield — like districts across Oregon — was off to a rocky start.

In early August, Springfield Public Schools announced that they had met the metrics to re-open for Kindergarten through third grade to return to in-person, making them the first and only district in Oregon with more than 10,000 students to decide to reopen the doors to grades K-3 (4th and above would continue to be online at least through the end of the calendar year). Educators in Springfield held a lot of mixed emotions about the decision. At first, Anne Goff was relieved. The former President of Springfield Education Association (SEA) was returning to the classroom after seven years of being in a full-time release role.

“I was completely torn. My first thought was ‘oh good.’ I don't want to teach online. I have no technology skills. I am a dinosaur. I hate technology and I don't think five and six-year-olds learn well in an online environment. But a few days passed, and there’s just become more and more evidence that, yes, children do get this disease. Yes, there’s been between 200 and 300 children who have died from this disease. So, it really changed my mind — as much as I don’t want to teach online, it is not safe for children and families and even myself… it’s not safe for any of us to be in the building,” Goff says.

Upsides and Downsides

Her fears were felt widely across the district, so much that when the decision to reopen was announced, SEA members bolted into action with an “It’s Too Soon” campaign. Members organized a car parade around downtown Springfield on the first of September, as well as a letter writing campaign directed at the Springfield School Board and upper administration. “Our signs said things like, ‘If it’s not safe for all grades, then it’s not safe for K-3,” says Springfield Kindergarten teacher Heather St. Louis. “We’re not saying we don’t want to be with kids — we do, very much – but we know it’s just not safe yet. We need a better plan and we need more time.”

St. Louis has been teaching in Springfield for four years at Riverbend Elementary School. Last March, when schools had to abruptly close their doors to children, St. Louis mourned the loss of time with her students. “Thinking back to that time, I remember feeling like I was grieving the end of the school year… even though I got to see my students every day on the computer, and we had built a relationship over the months we’d had together. But springtime in Kindergarten is such a special time — they’ve learned how to be students and are ready for so many more in-depth experiences. I was really sad to lose that because it’s kind of the prize at the end of the race,” she says.

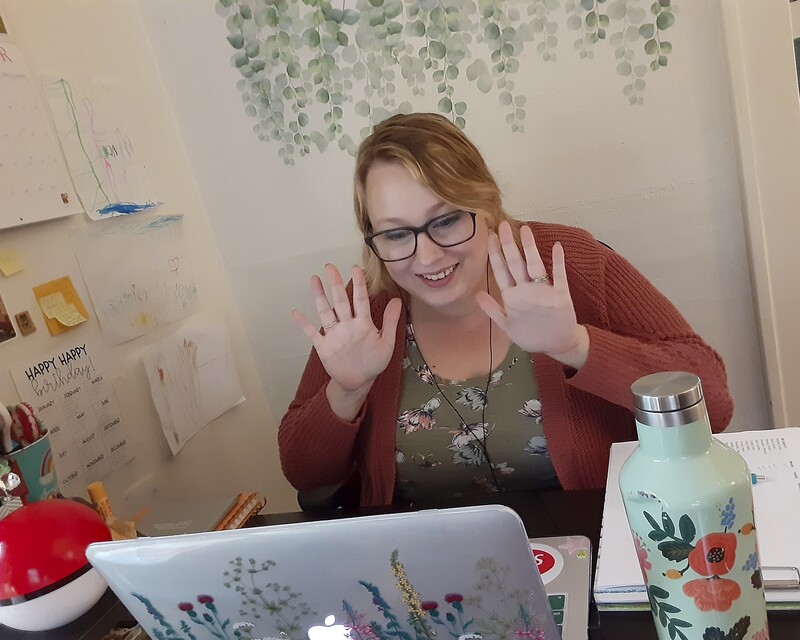

Heather St. Louis greets her 37+ SPS Online kindergarten students each morning from her dining room table.

This year, St. Louis was offered a Kindergarten teaching position at SPS Online, the district’s fully online (and now largest) elementary school. Teachers in the district who identified as high-risk for COVID-19 were allowed to join a lottery for SPS Online teaching positions, and St. Louis was fortunate to be one of the few who were offered a spot at the online school. Families were given the option to enroll their student in SPS Online if they wanted to guarantee a full year of distance/virtual learning (whereas keeping a student enrolled in their traditional school could mean a return to the classroom if the positive COVID-19 testing metrics dropped low enough). Enrollment numbers for SPS Online have continued to climb upward this Fall — as of press time, SPS Online was serving 972 elementary school students across the district.

For St. Louis, who serves as the building representative for SEA members working through SPS Online, the climbing enrollment numbers are not surprising, especially with the district’s haphazard beginning to the school year — families are looking for any semblance of stability. But, the numbers are also resulting in enormous class sizes for St. Louis and her SPS Online teaching colleagues. “Our class sizes are much larger than our building colleagues — for example, I have 37 kindergarteners. My Riverbend colleagues have large class sizes for the district and they currently have 16 students. There’s a big difference in equity there,” she says.

She says the glaring class size discrepancies wouldn’t have mattered quite as much if SPS Online had continued to operate with a self-paced, asynchronous model of teaching, as they have in prior years. Instead, the online school decided last month to align the curriculum with what’s being taught this year in all of the district’s elementary schools, which means there are points in the day where St. Louis and other SPS Online teachers are delivering synchronous instruction like their ‘in-building’ colleagues who are delivering Comprehensive Distance Learning (CDL).

“I love seeing my students face-to-face every day, but we’re doing this curriculum with double and triple the students (as those teaching through CDL), without a dedicated office staff. That starts to build up and you just get buried in a lot of administrative stuff, rather than planning and prepping for your students. When you have 40-plus students, and new ones are being added every day… you can imagine what that’s like,” she says.

St. Louis doesn’t take the position for granted, however, knowing she was one of the lucky few to have been drawn for a SPS Online teaching position. Her colleagues across the district are mixed in their reactions to being back in-building, first with the decision to bring back K-3, and even now, as they’re all teaching virtually in empty classrooms across the district.

Tricky Protocols

Aly Nestler, a 3rd grade teacher at Springfield’s Yolanda Elementary School, knows the struggle hits at all levels. Because the district had planned for a staggered start of K-3 (with third graders returning not until the first week of October), Nestler had been preparing her classroom for in-person instruction up until the day it was announced the district was moving to CDL. “Educators, and particularly early childhood educators, are going to the be first people to emphasize that in-person instruction is vital for our youngest learners, and our district leaders understand that. They really want to get kids back in school, not only for educational purposes but because they want to be providing meals for students, they want to be providing a safe space for students, and they know our families are really struggling with childcare, or need to work outside the home. These are all really challenging experiences for people with a lot of competing interests,” Nestler says.

But as teachers are being asked to come back into buildings, the conversation must also shift to include the health and safety of the staff who walk those hallways. Nestler says that over the summer, the district added additional safety measurers into the building to prevent the transmission of Coronavirus, including more hand sanitizing stations and air purifiers in every building. “They’ve given us these added measures of precaution, and yet we still don’t have enough staff to help monitor students and help them keep their masks on; we don’t have enough time between passing periods to actually use the hand sanitizing stations. We see all of the issues with the actual implementation of these protocols, and we worry that we might not have the resources, the training, or have had the time to truly understand how to do this appropriately. There’s lots of fairly basic logistical questions that are still unanswered,” Nestler says.

As educators know, each school had to submit a building blueprint to the Oregon Department of Education over the summer about their re-opening protocols. “Those plans look really good on paper. But we’re going to be spending our days with really young kids and are responsible for their care; what do you do when you have a Kindergartener who needs help zipping their jacket or tying their shoes or getting a band-aid put on their knee? Even in providing fairly basic care, we’ll be putting ourselves at higher risk,” Nestler says.

Three weeks now into the school year, and it’s really anybody’s guess how the rest of the year will unfold for educators in Springfield and across the state. Every teacher’s reality is slightly different from the next, but amidst the chaos, there are moments of sweetness and light. For St. Louis, who’s teaching from her dining room table, this comes with the opening chime she dings over the Zoom screen to get the attention of her nearly 40 Kindergarten students.

“The kids are delightful. When I’m with them, that part is familiar and wonderful. I love that part. It is different building that sense of community [online], but I'm trying to just translate what I would usually do at the beginning of year to this format,” St. Louis says. “I pull out my Pokeball filled with questions to ask during our morning meeting, I sing and do a lot of sign language. Even if they're on mute, I just make it very clear that I'm watching their lips move and I'm watching their faces. I have them do a lot of response with their hands. That’s just my little bag of tricks… I'm trying to just keep it like I would in the classroom.”

For Anne Goff, the daunting proposition of bringing tiny Kindergarteners into a highly controlled classroom space turned out to be much more joyous than she ever thought possible.

“I was truly trepidatious going back into the classroom — I thought it was going to be awful for children. I was worried they were going to feel like they were being punished because they had to stay in this little bubble of space and couldn’t really talk or play with their friends. [Before the year began] I said to my daughter, ‘I just may have to retire because this feels like I'm punishing children and I just I can't do it’,” she remembers.

But to her surprise, “instead it was quite joyful. They had a good time. At the end of my second day, one of my students told her mom she loved Kindergarten more than the Ferris wheel.”

Those six days serve as the capstone beginning to Goff’s sunset year of teaching. “I really wanted to end it in Kindergarten, which is where I started 33 years ago. This is certainly not what I expected, but being with kids is what makes all of the difficulties and the changes worth it.”